Sue Tyrannosaurus Rex: Life, Pathologies, and Controversy

email: noellemoser@charter.net

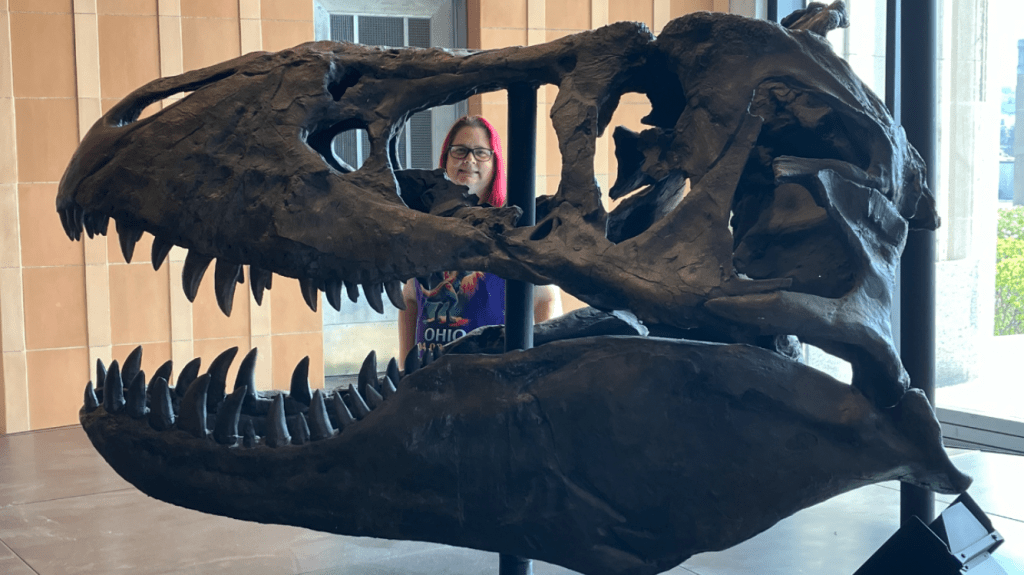

Everything about the Tyrannosaurus Rex overwhelms the human imagination. 50-60 bone-crushing teeth, a massive eight-ton weight, and formidable strength. Nothing can stop this terrestrial meat-eating machine, or so we think. Sue, the largest, most extensive, and best-preserved Tyrannosaurus Rex ever found, tells a different story. Sue had a hard life. Her remarkable skeleton tells of battle, disease, starvation, and the life lived by an old T-rex.

Discovery of Sue:

Sue’s story began in 1990. Scientists spotted bones protruding from a cliff face in South Dakota. These bones belonged to an adult Tyrannosaurus Rex. Scientists determined that 90% of the skeleton was present. This made the specimen (FMNH PR 2081) the most intact T-rex ever discovered. Named Sue, this tryannosaur became the subject of a heated dispute over legal ownership. Sue’s final resting place was on land the Sioux Tribe claimed belonged to them. However, Sue’s bones were on land that was held in trust by the United States Department of the Interior.

In 1992, Sue’s bones were seized by the FBI. The government transferred the remains to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. The skeleton was stored until the penal and civil legal disputes were settled. In October 1997, several large corporations and individual donors purchased Sue for 7.6 million dollars and transferred her to her new resting place at the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois.

Life of Sue and Pathologies visible in her bones:

Examination of the bones determined that Sue died at 28 years of age, one of the oldest Tyrannosaurus Rex known. During her life, Sue suffered many pathologies, including broken bones, torn tendons, broken ribs, bone infections, protozoan parasites, and arthritis.

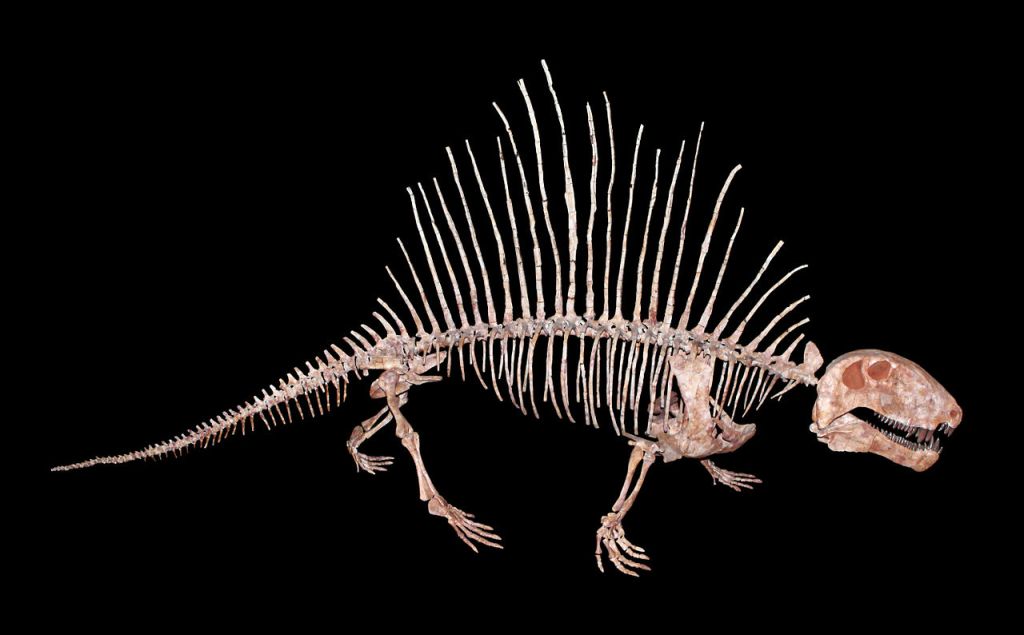

Sue allows us to get a glimpse of the life of Tyrannosaurus Rex, the king of the dinosaurs. An injury to the right shoulder region, likely from struggling prey, damaged the shoulder blade. It also tore a ligament in the right arm. Damage to ribs that healed shows that Sue survived this encounter. One of her most severe injuries is to the left fibula. The diameter is twice the size of her right fibula. This indicates that Sue suffered a bone infection from a serious injury. The injury was most likely from a horned or armored dinosaur.

The most fatal pathology seen in Sue’s skeleton is round holes in the lower jaw. The holes were from a trichomonas gallinae infection, a parasite that ate away at her bone. The infections cause swelling in the jaw and neck, resulting in death by starvation. It’s uncertain whether this was the fatal injury that ended Sue’s life. The agony from this pathology alone made it painful making ot hard for her to eat. Weighing 8 tons, Sue needed to consume an astounding number of calories to sustain her massive body. Unable to hunt or eat made it very difficult for her to survive. Tyrannosaurus Rex’s are social and hunt in groups. Given her advanced age at death, Sue was likely cared for by her social group.

As she progressed in age, Sue suffered from arthritis showed by fused vertebrae in her tail. Some reports state that she had gout, but this is still debated.

Sue’s fossil shows that the life of a Tyrannosaurus Rex was difficult, painful, and complicated. The king of the dinosaurs did not have it easy. Hunting heavily armored prey was dangerous. Fighting other Tyrannosaurus over territory or mating rights was precarious. Injuries that became infected proved deadly. Sue forces us to rethink how dinosaurs relate to each other. The Cretaceous was dangerous even for a Tyrannosaurus Rex.

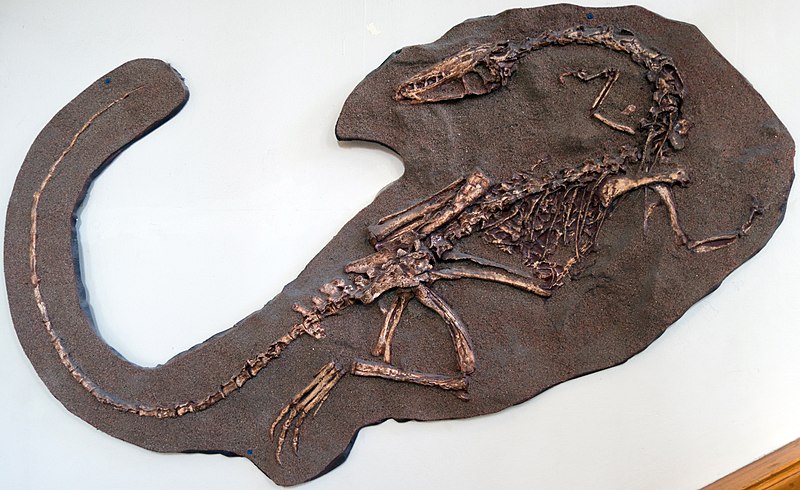

Death and Preservation of Sue’s Bones:

Sue died at 28 years of age. It is unknown how she died. But her skeleton poses likely scenarios. These include bone infections, starvation, or complications from parasitic disease. Preservation of her skeleton concludes that she died in a seasonal stream bed or flood. The flood washed away some of her bones. It jumbled the remaining skeletal parts together in a disarticulated manner. The sediment from the stream bed protected her body from scavengers preserving her skeleton quickly. This made her one of the most complete Tyrannosaurus Rex specimens ever discovered.

Sue is very important to paleontology and study of Tyrannosaurs Rex. Sue’s skeleton takes us back to a time when giants roamed the earth and allows us to see the life of T-rex. We can observe the injuries, diseases, and parasites that they encountered. Sue shows us that even the king of the dinosaurs had to scrape out life one day at a time. Life was challenging in the environment of the Cretaceous.

I write at the confluence of deep time and modern thought – a paleontology blogger and essayist devoted to translating ancient worlds for contemporary readers.

Through Coffee and Coelophysis, I explore the lives, mysteries, and afterlives of prehistoric dinosaurs, blending scientific curiosity with reflective story telling. I bring ancient fossils to life; across my other writing spaces, I explore literature, creative reflection, homesteading, backyard chicken keeping, and the lessons of observations.

In Shelf-Life: Lessons from Retail, the everyday world of retail becomes a stage where dinosaurs, books, and human stories collide – revealing how curiosity and wonder shape both past and present.

The Kuntry Klucker – A Blog About Keeping Backyard Chickens.

The Introvert Cafe – A Mental Health Blog

~ Noelle K. Moser ~

Resources:

Larson, Peter. Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. 2008.

Wikipedia Commons

My visit to The Field Museum. Chicago, Illinois.