Finding Depth in Dinosaurs: A Journey from Adornment to Archives

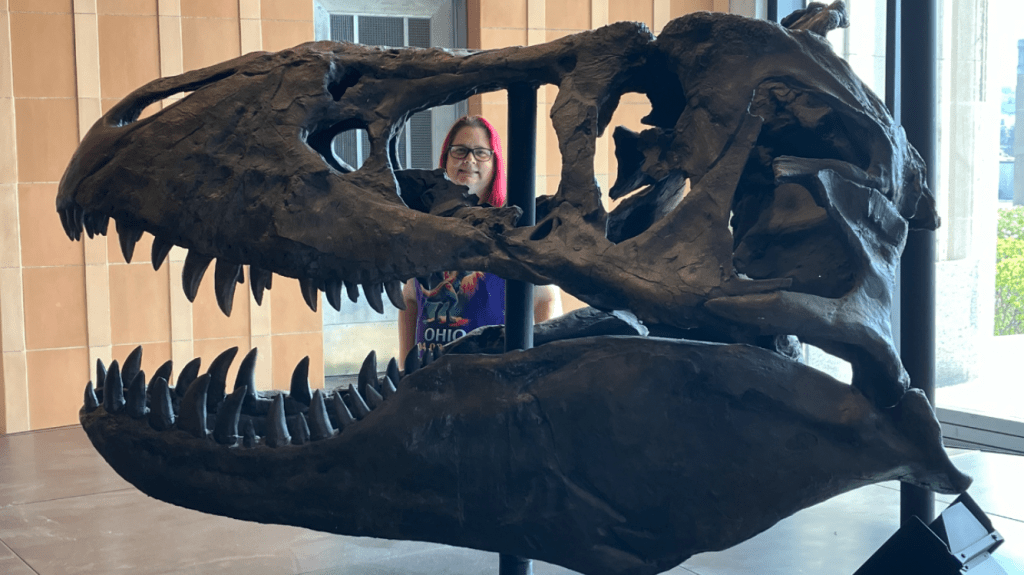

It has been some time since I last wrote within the fossil-rich corridors of Coffee and Coelophysis. Not because the passion diminished, or because the fascination with deep time, theropods, or the osteological poetry of extinct giants ever receded. But because the conditions required for this kind of writing became buried beneath the sediment of vocational life. Paleontological writing, I have come to realize requires a particular mental climate. It requires stillness, cognitive oxygen, and uninterrupted corridors of thought. And for a time, I found myself inhabiting a very different ecosystem.

The Biome of Adornment:

My previous professional habitat was one of adornment – a landscape structured around ornamentation, self-presentation, and the anthropology of display. It was an environment of rhinestones, polished metals, seasonal palettes and rotating aesthetics. On the surface, it may seem far removed from paleontology, and yet, even there, my mind refused to fully migrate. Because adornment, when examined through an evolutionary lens, is not foreign to prehistoric thought.

Display structures dominate the fossil record of behavior. The crest of Allosaurus, horns of Triceratops, feathers of Archeopteryx, and the coloration of today’s dinosaurs – birds.

I often found myself thinking – sometimes idly, sometimes analytically about the continuity between human ornamentation and Mesozoic display behavior. Earrings became analogues to integumentary signaling, hair accessories echoed plumage, and jewelry functioned as modern exaltations of ancient display instinct.

Even in a biome dominated by surface aesthetics, my thoughts drifted persistently toward bone, integument, and evolutionary signaling. The paleontologist never left, she simply observed quietly. Told through the ancient wisdom of dinosaurs, field notes from my time in accessory retail are chronicled in a blog entitled Shelf-Life: Lesson from Retail.

Writing in Fossil Suspension:

Despite that continuity, something within me entered a state best described as fossil suspension. My writing did not go extinct, it fossilized. Buried beneath the comprehensive weight of retail space, social performance, and cognitive fragmentation, the deeper analytical voice that fuels this blog entered preservation mode-intact, but inaccessible.

Fossilization, after all, is not destructive. It is deferred revelation. And like any specimen awaiting excavation, the writing remained, waiting for the right sedimentary pressure to lift.

Following the Fossil Trail:

When the shift finally came, it did not feel like escape, it was track following. Paleontologists know the intimacy of trackways, the act of tracing fossilized footprints across lithified ground, step by step, reconstructing the movement of a lifeform long vanished. My vocational transformation felt much the same. I did not abandon one ecosystem so much as follow a fossil trail toward another.

Each step marked by subtle signals, a resurgent desire to think and read more deeply, growing hunger to write, mental fatigue from surface engagement, and a longing for intellectual stratification. Instinct-that ancient navigational system shared by migratory species-took hold. And it led me, trackway by trackway, toward archives and tomes.

Entering the Archive Biome:

I now work within tome retail. An environment that, while not a museum or dig site, operates within the same preservation philosophy. Where adornment retail curated surface, archive retail curates memory. Where one displayed object of identity, the other houses narratives of existence.

Stories like fossils, are preservation technologies, they hold life in suspension across time. I no longer pierce adornments into bodies; I place stories in hands. In doing so, I find myself participating once again in the work of temporal preservation-the safeguarding of knowledge, wonder, and deep time literacy.

Vocational Proximity to Dinosaurs:

It would be easy to assume that because I am not currently in a museum lab, a prep room, or a field excavation, I exist at a distance from paleontology. But distance from dinosaurs is not measured in miles from fossil beds, it’s measured in cognitive proximity to the conditions that allow them to live in the mind.

Tomes reduce that distance, rather they restore by increasing reading stamina, research access, writing energy, and intellectual curiosity. They create an atmosphere where prehistoric life can breathe again, not in bone, but in thought.

Dinosaurs, for me, have always functioned as a vocational compass – a fixed point in deep time against which I measure the alignment of my life.

When I drift too far into environments that prioritize velocity over reflection, trend over truth, and surface over structure, I feel their absence like oxygen deprivation. But place me among books, archives, histories, preserved narratives and they return immediately, not as relics but as guides.

Preservation, Not Destination:

This migration into tomes and archives is not an endpoint. It is a supportive biome, one that funds, nourishes, and stabilized the intellectual life required to pursue paleontology with depth and integrity.

The fossil trail does not end with tomes, it passes through on its way back to research, writing, museums, and field sites. To wherever the next excavation of self and prehistory awaits.

In the meantime, I remain in vocational orbit around the creatures who have always oriented my internal compass, reading, writing, and still chasing dinosaurs.

I want to close this reflection not in dismissal of the ecosystem that came before, but in gratitude for it. Adornment retail was not a detour from my path, it was a formative stratum within it. It taught me to observe human behavior, to lead, to communicate, to endure high-velocity environments, and to recognize the anthropology of display in ways I might never have studied otherwise. Even there, among headbands and scrunchies, the paleontologist in me remained awake, watching, interpreting, and learning.

For that, I am thankful. But gratitude and belonging are not always the same thing. Because if the former biome was one I learned to survive within, the new one is where I instinctively breathe.

Within the archive corridors of tomes among shelves that function like stratigraphic layers and stories that preserve life across time, I feel a cognitive and creative homecoming that is difficult to articulate but impossible to ignore.

I do not feel displaced here, I feel situated, and aligned. As though I have stepped into an environment where the deeper architecture of who I am as a reader, writer, and paleontological thinker is not merely accommodated, but oxygenated.

Adornment taught me much, archives restore me. And from this restored ground, the fossil trail continues forward, deeper into writing, research, and ever closer to the ancient creatures who have always oriented my vocational compass – Dinosaurs.

I write at the confluence of deep time and modern thought – a paleontology blogger and essayist devoted to translating ancient worlds for contemporary readers.

Through Coffee and Coelophysis, I explore the lives, mysteries, and afterlives of prehistoric dinosaurs, blending scientific curiosity with reflective story telling. I bring ancient fossils to life; across my other writing spaces, I explore literature, creative reflection, homesteading, backyard chicken keeping, and the lessons of observations.

In Shelf-Life: Lessons from Retail, the everyday world of retail becomes a stage where dinosaurs, books, and human stories collide – revealing how curiosity and wonder shape both past and present.