Stan the T-Rex: History and Mystery of a Fossil Star

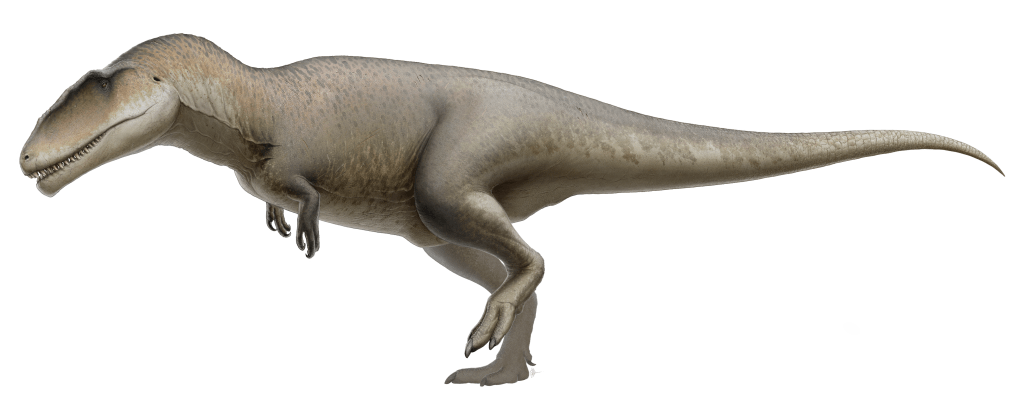

Since the first Tyrannosaurus Rex specimen was discovered in 1902, this theropod has captured the human imagination worldwide. Despite the popular belief that Tyrannosaurus Rex is a homogenous species, each of the 50 Tyrannosaurus Rex specimens displayed in museums worldwide represents unique individuals.

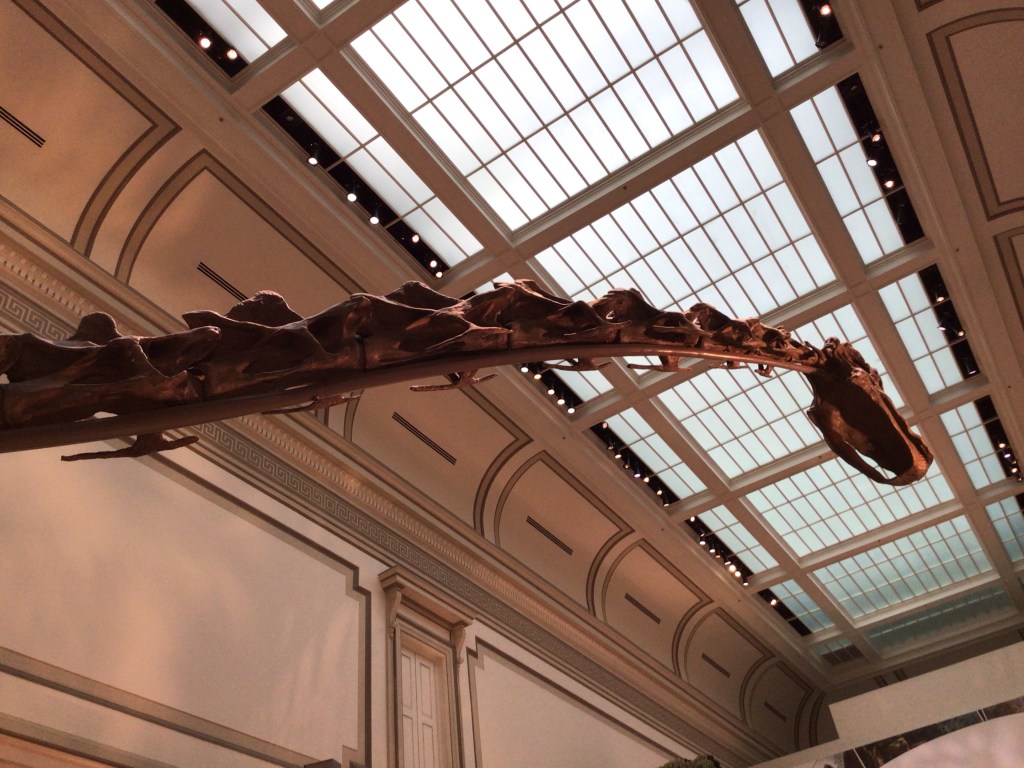

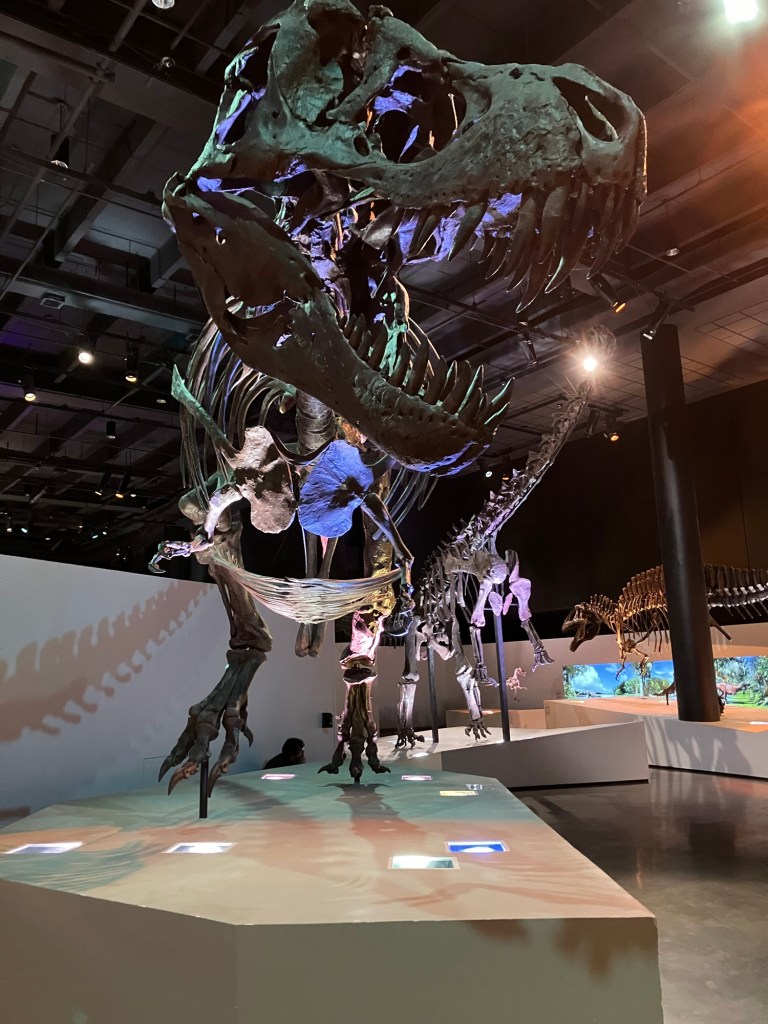

Image Credit: Noelle K. Moser. Tyrannosaurus Rex MOR 555 (Walter) and Triceratops. National Natural History Museum. Washington, D.C.

Tyrannosaurus Rex is the most popular but least understood dinosaur of the Mesozoic. The war still rages on whether T-rex was an opportunistic scavenger or the cold blooded butcher of the Cretaceous. While no carnivore would pass up a free meal, the teeth suggest that the T-rex could kill and consume meals whole with bone-crunching force. Mischaracterized as a mindless brute solely focus on killing, this intelligent animal was social and possessed the complex capability to live in social groups.

Furthermore, some studies suggest that Tyrannosaurus rex may have been more than just a fearsome predator—it could have also been a devoted partner. Take Sue, one of the most iconic T. rex specimens: her skeleton is marked with numerous injuries, some quite severe, yet evidence of calcium deposits indicates significant healing. While Sue’s survival likely speaks to her own resilience, comparisons with modern birds—T. rex’s closest living relatives—raise the possibility that she may have been tended to by a loyal companion during recovery.

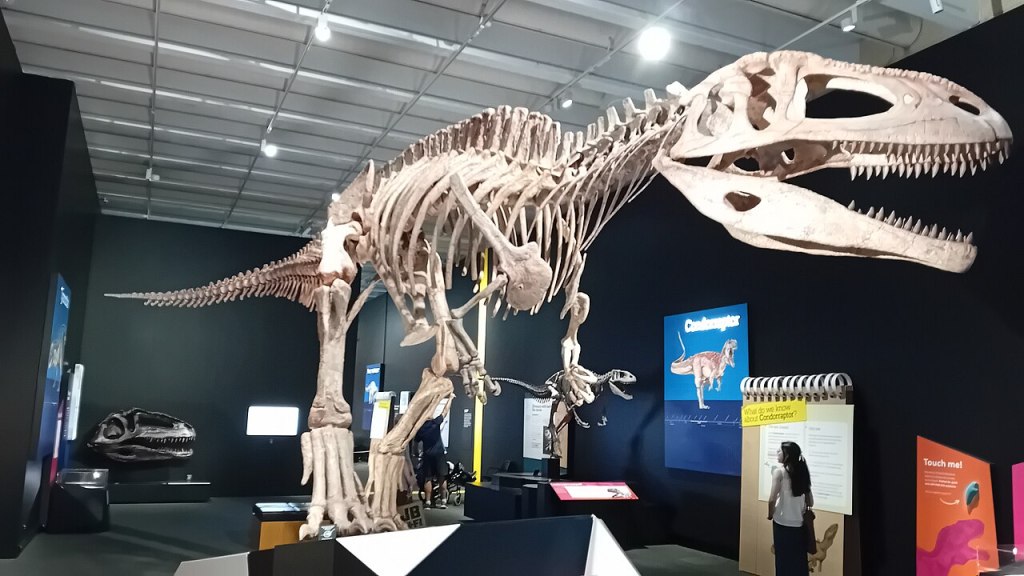

Despite all we’ve uncovered about the iconic Tyrannosaurus rex, much about this formidable predator remains shrouded in mystery. With each new discovery, we gain deeper insight into its biology and behavior. Stan, in particular, gave us an unprecedented look at what may be evolution’s most advanced anti-tank weapon—a predator equipped with bone-crushing strength and armor-piercing teeth capable of breaching even the most well-defended dinosaurs.

Contrary to the long-held image of Tyrannosaurus rex as a solitary predator that only sought out others to mate, recent research paints a far more social picture. Rather than roaming alone through the Late Cretaceous landscape, T. rex may have hunted in coordinated groups. If a single T. rex lurking in the underbrush is terrifying, imagine a pack working together to ambush their prey. The idea of these apex predators operating as a unit is enough to send shivers down the spine of anything unfortunate enough to cross their path.

Studies on Stan and other robust Tyrannosaurus Rex fossils, suggest that the T-rex’s intelligence was among the highest, akin to that of Deinonychus (Velociraptor) in terms of social intelligence, enabling them to cooperate in packs for hunting and nurturing their young.

This massive and intimidating theropod, renowned for its bone-shattering bite, was both highly social and remarkably intelligent. Today, the mighty Tyrannosaurus Rex is recognized as a cunning and formidable predator, rightfully earning its crown as the undisputed King of the Dinosaurs.

Each Tyrannosaurus Rex tells a unique story captured in stone. Their bones whisper tales of thrilling lives, injuries, illness, dramatic and sometimes violent deaths, each different from the next. This article embarks on an exciting journey into the world of the Tyrannosaurus Rex, featuring the fascinating story of one of its most famous fossils, BHI 3033, also known as Stan.

The Story of Stan:

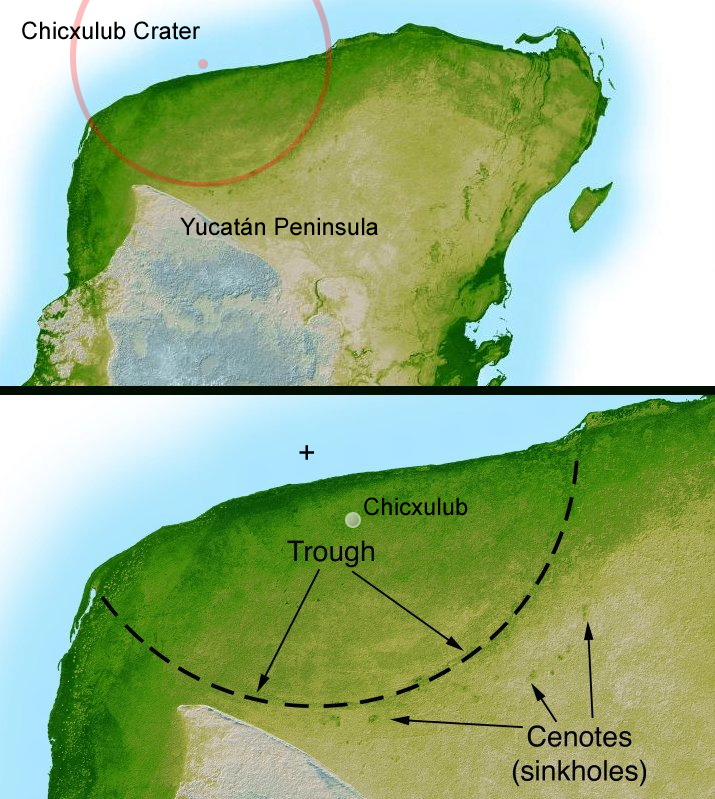

In 1987, deep beneath the K–T boundary in the Hell Creek Formation near Buffalo, Harding County, South Dakota, a remarkable discovery waited in silence—16 meters underground, laid Stan, entombed for 66 million years. Excavation of his fossil began on April 14, 1992, led by the Black Hills Institute, and was completed by May 7 of the same year. Cataloged as BHI 3033, the specimen was named “Stan” in honor of its discoverer.

After more than 30,000 hours of detailed preparation, Stan made his public debut in June 1996. His first appearance was on an international tour in Japan, captivating audiences across the globe. Today, Stan remains one of the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons ever unearthed, providing an extraordinary window into the anatomy and behavior of this iconic predator.

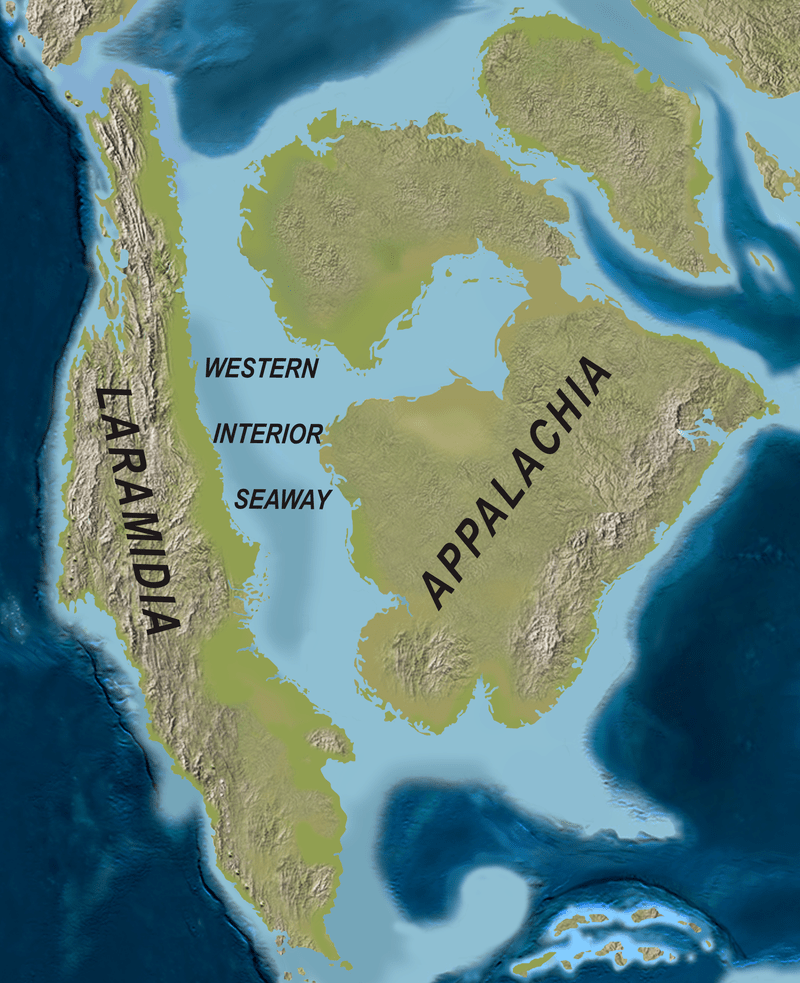

Life in Hell Creek During Stan’s Life:

Life in the Hell Creek Formation during the Late Cretaceous—around 66 million years ago—was vibrant, dynamic, and full of drama. It was a lush, subtropical environment with a warm, humid climate, lots of rainfall, and diverse ecosystems including coastal plains, swamps, rivers, and forests. Very silmilar to the bayous of Louisiana and the Pacific Northwest today.

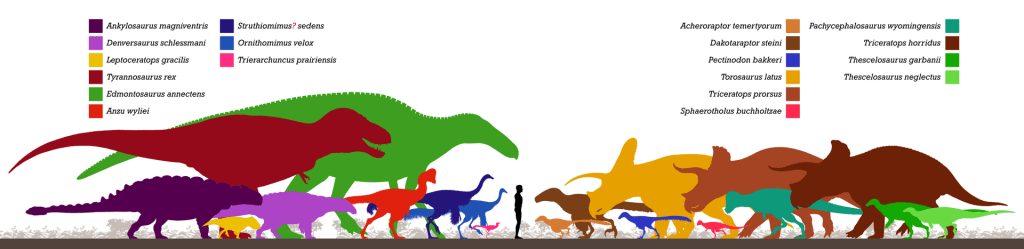

Living along side Stan were a variety of paleoflora and paleofauna. Some of the most recognizable dinosaurs shared this ecosystem.

Triceratops – Herd-dwelling horned dinosaurs, likely locking horns over mates or territory.

Edmontosaurus – Large, duck-billed hadrosaurs, probably migrating in herds and grazing like prehistoric cattle.

Ankylosaurs and pachycephalosaurs – Armored tanks and dome-headed headbutters roaming under the cover of trees.

Small theropods like Troodon and Dromaeosaurus – Agile predators or opportunistic omnivores.

Other Life Living In Hell Creek with Stan:

Crocodilians like Borealosuchus – Lurking in the water, ambushing anything that got too close.

Turtles, amphibians, and early mammals – Filling ecological niches on the ground, in trees, and even underground.

Pterosaurs – Soaring above the forests, especially near waterways.

Birds – Already fairly modern in form, flitting through the canopy or diving for fish.

Paleofauna of Hell Creek:

The paleoflora of the Hell Creek Formation during the Late Cretaceous was incredibly rich and diverse. It reflected a humid, subtropical to warm temperate climate, with a strong influence from nearby coastlines and river systems. The vegetation was a mix of ancient holdovers and newer, flowering plants, painting a picture of a world in ecological transition.

Recognizable and common plants thriving in Late Cretaceous Hell Creek.

Angiosperms (Flowering Plants)

Platanaceae (sycamore relatives)

Magnoliaceae (magnolia-like plants)

Lauraceae (laurel family)

Fagaceae (beech/oak relatives)

Conifers (relatives of evergreen trees)

Ferns and Tree Ferns

Mosses and Liverworts

The vegetation of Hell Creek supported a complex web. These plants also helped form the distinctive layered stratigraphy of Hell Creek, especially with leaf litter, root systems, and decaying wood contributing to the fossil record.

The audio landscape of Hell Creek was vibrant and diverse. The buzz of large insects, chirps, and dinosaur calls echoing across the floodplains, and maybe the distant rumble of a thunderstorm rolling in from the coast. Life was beautiful and brutal.

Daily Life In Late Cretaceous Hell Creek:

Using our minds eye and evidence from the fossil record, we can construct a plausable scenario from Stan’s perspective in Late Cretaceous Hell Creek.

Let’s drop into a moment in Hell Creek—quiet, moody, and full of tension just under the surface.

It’s early morning. A pale sun pushes through low clouds, casting a gauzy light across the misty floodplain. The air is heavy with moisture, thick with the scent of wet ferns, rich soil, and the musk of animals you can’t yet see. Somewhere in the distance, a chorus of frogs sings its final notes before the heat rises. A breeze rustles the leaves of broad-leaved magnolias and ginkgoes, sending tiny droplets scattering from the canopy like diamonds.

You’re standing at the edge of a slow-moving river, its banks muddied by last night’s rainfall. A snapping turtle eyes you warily before vanishing beneath the surface with barely a ripple. Dragonflies hover above the reeds like flickering ghosts, their wings catching light that breaks through the trees.

Suddenly, the brush on the other side of the water shifts. A young Edmontosaurus steps out, its nostrils flaring, scenting the air. Its massive, pebbly hide is dappled with dew and the shadow of leaves. It cranes its neck, listening, before lowering its head to drink.

Then—a silence. Not peaceful, but alert. A flock of early birds bursts from the trees with a shriek. The Edmontosaurus jerks upright, trembling. Across the clearing, between two tree trunks as wide as a truck, a shape stirs.

Out steps Stan. Not charging. Just there. Quiet. Intent. His skin is mottled, mud-streaked, speckled with insects and scars from battles with other tyrannosaurs in the area. Each footfall is heavy but controlled, barely making a sound on the damp earth. His eyes are fixed on the hadrosaur—not wild with hunger, but cold and assessing.

The Edmontosaurus bolts.

In a flash of spray and crashing reeds, Stan lunges after it, jaws parted just enough to reveal evolution’s most advanced anti-tank weapon—a predator equipped with bone-crushing strength and armor-piercing teeth capable of breaching even the most well-defended dinosaurs. The trees shudder with the pursuit. A burst of birds takes flight, and somewhere in the distance, an unseen Triceratops bellows like thunder.

Then, silence again. The floodplain breathes.

Hell Creek wasn’t just a jungle full of dinosaurs—it was also the scene of an impending catastrophe. The ecosystem was thriving but balanced on a knife’s edge, and just before the asteroid impact, you’d never know extinction was looming.

What Remained of a Fossil Star?

It is unclear how Stan died. Based on the preservation of his skeleton, Stan died near a water source as his body was fossilized relatively quickly with minimal signs of scavenging by ofher animals living in Hell Creek at his death.

“The Hell Creek Formation during the Late Cretaceous represented a fluvially dominated floodplain system. The high water table and frequent sedimentation events within this environment facilitated exceptional fossil preservation, as evidenced by specimens such as Tyrannosaurus rex individuals Stan and Sue.” (Johnson, Nichols, Hartman. 2002).

The cometeness of Stan’s skeleton totalled 190 bones, or 63% of the skeleton by bone. (Larson, 2008).

Preserved skeletal elements of Stan include:

A nearly complete skull,

59 vertebrae (9 cervical, 14 dorsal, 5 sacral, 31 caudal);

24 cheverons;

14 cervical ribs;

12 dorsal ribs;

Anearly complete pelvis;

Left femora (femor or thigh bone);

Both tibiae;

Both calcanea;

Astragali;

Left metatarsals; and

11 pes phalanges.

The prehistoric story preserved in Stan’s bones:

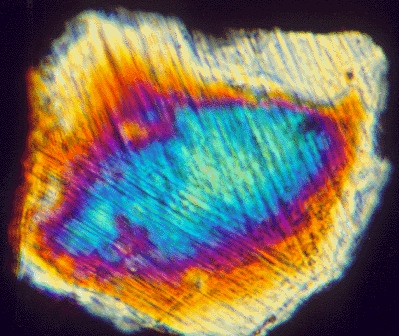

Stan’s fossil tells a compelling story of adversity, injury, determination, and survival. Among the most striking findings is the presence of fused cervical vertebrae, which clearly indicates that at some point in his life, he was bitten by another T-rex.

The fossil record demonstrates that tyrannosaurs engaged in face biting, a well-documented ritualistic behavior in the fierce competition for mating rights. The calcium deposits found in Stan’s bones confirm that he not only survived this injury but healed from it. However, the fused vertebrae likely caused him discomfort for the rest of his life, underscoring his resilience and tenacity in the face of challenges.

The Cretaceous period posed significant challenges for the Tyrannosaurus Rex. As the undisputed King of the Dinosaurs, T-rex had its advantages, but it was not immune to the hidden dangers of Mesozoic life. Just like today, parasites were a prevalent issue for dinosaurs, and Stan was no exception. Bone infections caused by Trichomonas protozoan—common parasites found in both birds and dinosaurs—were evident, marked by distinct round holes on the jaws of several T-rex specimens. These infections led to inflammation and pain, which undoubtedly affected their hunting and feeding efficiency.

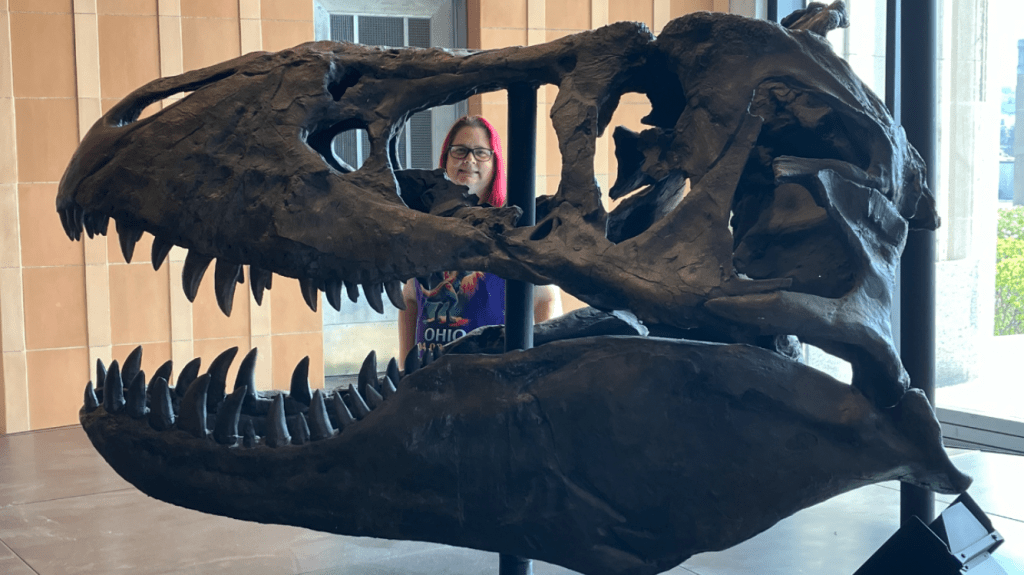

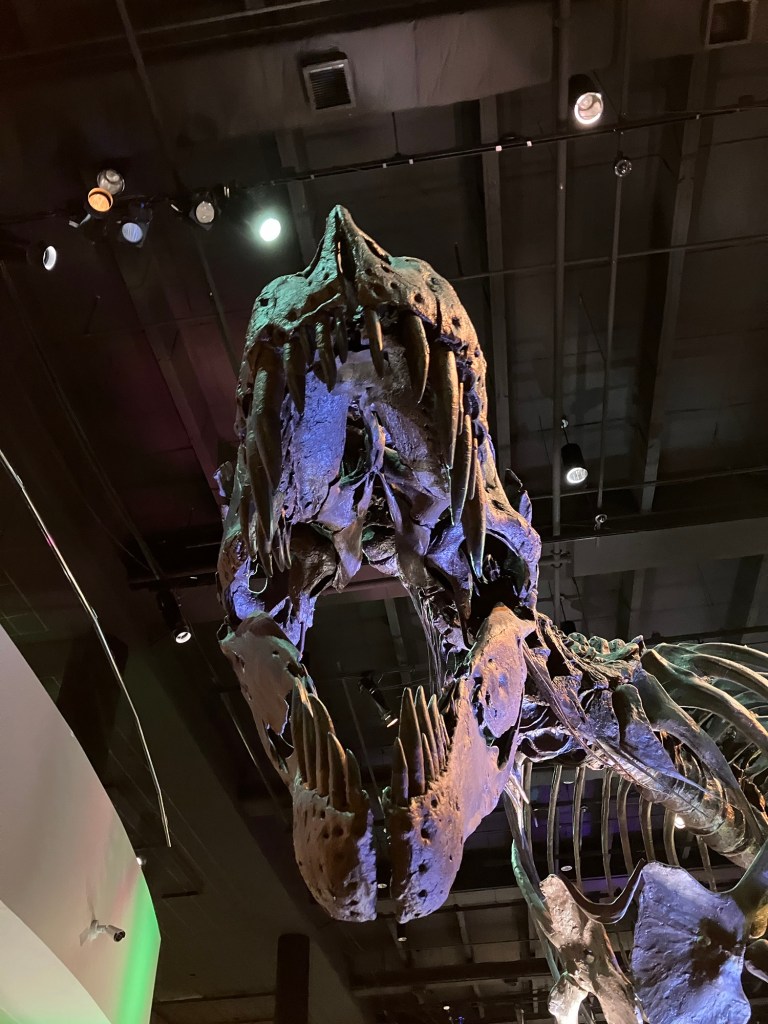

Most Complete Tyrannosaurus Rex Skull

Stan’s fossil has yielded valuable insights into the intricate structure of a Tyrannosaurus rex skull. Exceptionally well-preserved, it has enabled scientists to create a brain cast from the brain case associated with this specimen. Much like in humans, the brain leaves distinct impressions on the interior of the skull, allowing for a detailed examination of its anatomy.

Studies of these brain casts indicate that the T. rex possessed a notably large auditory lobe, particularly attuned to low-frequency sounds below 40 Hz. This finding not only suggests that Tyrannosaurus rex could hear such low sounds but also raises the possibility that it could produce them. While humans are unable to perceive sounds below 20 Hz, one would likely be able to sense the vibrations from a T. rex’s vocalizations if encountered in its natural environment.

Stan provides an extraordinary insight into what could be considered one of evolution’s most advanced anti-tank weapons—a formidable predator characterized by its bone-crushing strength and armor-piercing teeth, which were capable of penetrating even the most well-defended dinosaurs. The ongoing debate about whether Tyrannosaurus rex was primarily a hunter or a scavenger continues to capture the interest of dinosaur enthusiasts. Dental adaptations clearly indicate that Stan was well-equipped to crush bones and consume prey whole with remarkable efficiency.

With conical, serrated, and recurved teeth resembling a set of razor-sharp steak knives, Tyrannosaurus rex was perfectly adapted to tear large chunks of flesh from its prey. Lacking molars and grinding teeth, it likely swallowed these meals whole while using its immense bite force to crush bone. The extraordinary fossil evidence from Stan has reshaped our understanding of T. rex, offering compelling insights that challenge the notion of this fearsome predator as merely an oversized scavenger.

I write at the confluence of deep time and modern thought – a paleontology blogger and essayist devoted to translating ancient worlds for contemporary readers.

Through Coffee and Coelophysis, I explore the lives, mysteries, and afterlives of prehistoric dinosaurs, blending scientific curiosity with reflective story telling. I bring ancient fossils to life; across my other writing spaces, I explore literature, creative reflection, homesteading, backyard chicken keeping, and the lessons of observations.

In Shelf-Life: Lessons from Retail, the everyday world of retail becomes a stage where dinosaurs, books, and human stories collide – revealing how curiosity and wonder shape both past and present.

References:

Kirk R. Johnson, Douglas J. Nichols, Joseph H. Hartman, 2002. “Hell Creek Formation: A 2001 synthesis”, The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the northern Great Plains: An Integrated continental record of the end of the Cretaceous, Joseph H. Hartman, Kirk R. Johnson, Douglas J. Nichols.

Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth. Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. 2008.