Carcharodontosaurus Saharicus: Shark-Like Teeth and Massive Size

email: noellemoser@charter.net

Millions of years before Tyrannosaurus Rex roamed the earth, another group of gigantic meat-eaters ruled the land. This group of dinosaurs produced some of the largest carnivores, Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, Acrocanthrosaurus, and Tyrannotitan.

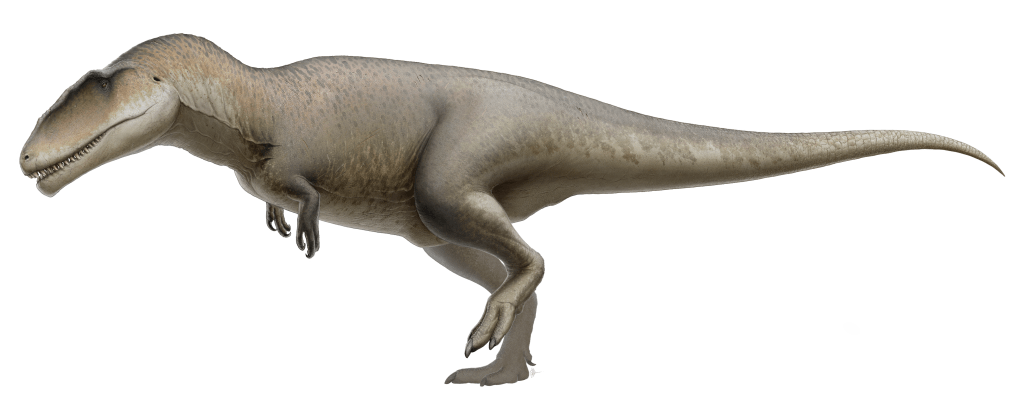

Roaming North Africa 99 to 94 million years ago, Carchrodontosaurus (CAR-car-oh-DONT-oh-SORE-us) reached massive sizes, some outweighing Tyrannosaurus Rex by a ton. While size alone places this theropod in the Dinosaur Hall of Fame, the most remarkable characteristic of this massive meat-eating machine is the teeth of this carnivore.

Shark-Like Teeth of Charcharodontosaurus.

Weighing seven metric tons, Carcharodontosaurus had a ferocious apatite, armed with 60 sharp recurved, serrated teeth that bear a striking resemblance to that of a great white shark – and inspiration for the name – this massive meat-eater effortlessly sliced and diced large titanosaurs which it hunted in family groups. Even more captivating was the discovery of Carcharodontosaurus.

Discovery of Carchrodontosaurus:

In 1699, Edward Lhuyd found a tooth thought to have belonged to a large extinct carnivorous fish. Subsequent studies showed that the tooth belonged to an unknown species of Megalosaurus. In 1824, William Buckland, an English Theologian, geologist, and paleontologist, discovered the first dinosaur fossil, Megalosaurus (meaning “great lizard”). The fossil recovered contained the lower mandible (jawbone) and teeth of a large theropod from the Middle Jurassic about 166 million years ago. William Buckland described the teeth as sharp, serrated, and jagged, similar to the shark tooth found by Edward Lhuyd nearly 100 years earli

Tracking across Egypt in 1914, German paleontologist Ernest Stromer and his expedition team excavated a partial skeleton of a large theropod with shark-like serrated jagged teeth described as Megalosaurus saharicus, belonging to a group of theropods called Megalosauridae.

After careful study, in 1931, Stromer announced that the tooth belonged to a new species of carnivorous theropod dinosaur he called C. saharicus (Carcharodontosaurus Saharicus). Unfortunately, the skeleton was destroyed by Allied bombing raids during the Second World War. C. saharicus was lost to science until 1995 when a complete skull was excavated from the Kem Kem Beds in Morocco.

Size:

Stromer hypothesized that C. saharicus was around the same size as the tyrannosaurid Gorgosaurus, which was 26–30 ft long, 39–41 ft head to tail, and weighed approximately 5–7 metric tons. Carcharodontosaurus saharicus is one of the largest known theropod dinosaurs and terrestrial carnivores.

Feeding and Diet:

Bite forces of Carcharodontosaurus and other giant theropods Acrocanthosaurus and Tyrannosaurus were analyzed showing that carcharodontosaurids had much lower bite forces than Tyrannosaurus despite being similar in size. A 2022 study estimated that the anterior (front teeth) bite force of Carcharodontosaurus was 11,312 newtons while the posterior (back teeth) bite force was 25,449 newtons, suggesting that it did not eat bones.

The shark-like teeth of Carcharodontosaurus acted like a meat slicer, while the conical-shaped teeth of Tyrannosaurus Rex crushed bone. Acrocanthosaurus (another carcharodontosaurid) relied on pack cooperation with a slice-and-dice approach to hunting. The theropods trailing behind a large herd of sauropods would take turns biting and slashing at the target; the objective was to keep the prey moving and bleeding. The lumbering prey, weakened through blood loss, exhaustion, and infections, would collapse under its weight. Like Acrocanthosaurus, this suggests that Carcharodontosaurus used this same hunting method.

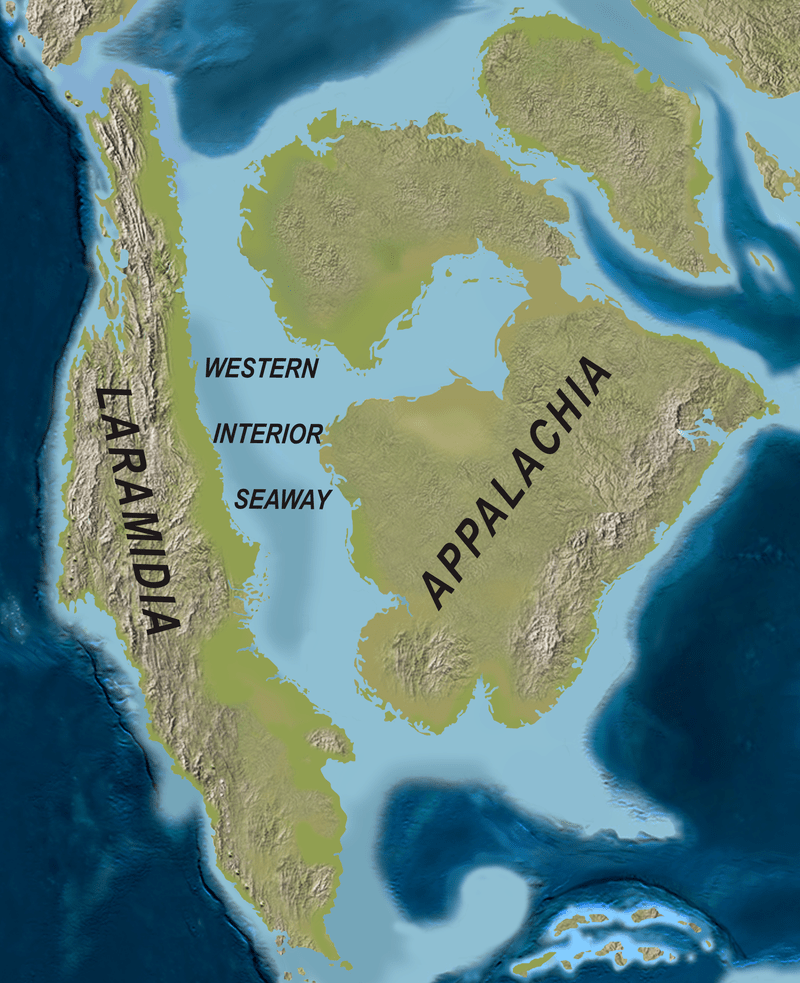

Paleoenvironment:

Carcharodontosaurus fossils reside in Cretaceous-age formations across North Africa. During the Cretaceous, North Africa, bordered by the Tethys Ocean, occasionally flooded and created an environment of tidal flats and lush waterways. The seasonal monsoons created sub-tropical environments supporting diverse fauna. Unlike other regions, Cretaceous North Africa is an anomaly as several groups of meat-eating dinosaurs lived nearby. Fossil records show that niche diets allowed the habitat to support fewer herbivores per carnivore ratio. Fish-eating dinosaurs such as Spinosaurus hunted in the water while land-dwelling theropods hunted on land. Simply put, the carnivorous dinosaurs did to compete for food.

Extinction:

For unknown reasons, the tyrannosaurs (Abelisaurs in the Northern Hemisphere, Tyrannosaurs Rex in the Southern Hemisphere) replaced Carcharodontosaurus and the other predatory theropods Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Acrocanthosaurus. The remaining tyrannosaurs ruled the land for 3.6 million years until that fateful day 66 million years ago.

I am a multi-disciplinary writer, blogger and web content creator. If you liked this post, please visit my online writing portfolio and other sites.

The Kuntry Klucker – A blog about raising backyard chickens

The Introvert Cafe – A Mental Health Blog

~ Noelle K. Moser ~

Resources:

Natural History Museum Carcharodontosaurus

Ransom-Johnson, Evan & Csotonyi, Julius. Dinosaur World. Kennebunkport, Maine, Applesauce Press, 2023.

Wikipedia: Charcharodontosaurus

My visits to Natural History Museums across the country.