Medullary Bone: Tracing the Reproductive Tissue Link between Tyrannosaurus Rex and Egg-Laying Hens

noellemoser@charter.net

Since the discovery of the holotype Tyrannosaurus Rex in 1902 by Barnum Brown in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, no other dinosaur has captured the human imagination. Upon its discovery, Barnum Brown wrote this to Henry Fairfield Osborn, friend, and curator of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. “It is as if a child’s conception of a monster had become real and was laid down in stone” (Randall, 2022).

Though most of the skull and tail were missing, everything about this monster would overwhelm the human imagination. The specimen that Brown found stood 13 feet tall at the hips, its jaws measured over 4 ft in length, and would have weighed 6-8 tons. This was the only known specimen to science and was given the appropriate name Tyrannosaurus Rex by Henry Osborne in the fall of 1902. Tyrannosaurus which means “tyrant lizard” in Greek and “rex” which means “king” in Latin; Tyrannosaurus Rex, the king of the lizards, no other name would capture in two words the sheer power contained within this beast.

We crave to learn all we can about the largest therapod dinosaurs that ever existed. Over the past one hundred years, we have gleaned a wealth of information from the fifty Tyrannosaurus Rex specimens currently housed in museums around the world.

Tyrannosaurus rex gender is a tribute to the founder of the specimen. Sue (FMNH PR2081), discovered in 1990 by Sue Hendrickson, the largest and most complete Tyrannosaurus-rex, is aptly considered female. Stan (BHI 3033), discovered in 1987 by Stan Sacrison, containing the most complete skull, is considered male.

While these attempts to assign a pronoun to tyrannosaurus specimens offer a sense of personhood, a link to the actual gender of tyrannosaurus rex specimens rests in the most unlikely of places – chickens.

Birds are dinosaurs. Specifically, birds are a type of therapod rooted in the dinosaur family tree that contains the same ferocious meat-eaters as T-rex and Velociraptor (Brusattee, 2018). Birds lie within an advanced group of therapods called paraves – a subgroup of therapods that traded in the brute body plan of their gargantuan ancestors for larger brains, sharpened acute senses, and smaller, lighter bodies that permitted progressive lifestyles above their land-dwelling relatives. Anatomically, chickens and tyrant theropods have many common characteristics that define the body plan of these magnificent creatures.

Air Sacs:

Birds achieve flight by two fundamental anatomical adaptions – feathers and hollow bones. While feathers provide the ability to soar above our heads, the real secret lies in their bones. Saurischians – the line of the dinosaur family tree containing both the giant sauropods and therapods – possessed skeletal pneumaticity – spaces for air in their bones. Skeletal pneumaticity produces hollow bones that lighten the skeleton, allowing for a wide range of motion. For example, without pneumaticity, sauropods would not be able to lift their long necks, and giant therapods would lack agility and ability to run because their skeletons would be far too heavy. In birds, air sacs are an ultra-efficient lung oxygen system. This flow-through inhalation and exhalation provides the high-energy birds need during flight. Evolving one-hundred million years before birds took flight, this is the true secret to their ability to take to the skies.

The signature feature of birds – feathers – evolved in their ground-dwelling theropod ancestors first noticed in Sinosauropteryx, the first dinosaur taxon outside parades to be found with evidence of proto-feathers.

The earliest feathers looked much different than the quill feathers of today. Initially, feathers evolved as multipurpose tools for display, insulation, protection for brooding, and sexual dimorphism. These early feathers were more like a fluff – appearing more like fur than feathers – consisting of thousands of hair-like filaments. Silkie chickens possess feathers that lack barbs that form the classic shape we associate with feathers. The first proto-feathers in dinosaurs were much like the texture of feathers on the Silkie. The breed name “Silkie” is derived from this unique feather texture.

Wings:

While large theropods like Tyrannosaurus Rex noticed diminishing forearms throughout the Mesozoic, other dinosaurs like Zhenyuanlong and Microraptor traded in forearms for wings.

Despite possessing wings, these feather-winged dinosaurs could not fly. Their bodies were far too heavy to achieve flight observed in birds today. Aboral dinosaurs glided from tree to tree or used their wings to fly flop on the ground. These first fully feathered dinosaurs also used their plumage as display features to attract mates or frighten enemies, as stabilizers for climbing trees, and protection and warmth for brooding offspring.

As the body plan for feathered dinosaurs continued to fine-tune the use of feathers, flight happened by accident. More advanced paravians had achieved the magical combination to achieve flight – large wings and smaller bodies (Brusatte, 2018). As the body plan of birds continued to refine, they lost their long tails and teeth, reduced to one ovary, and hollowed out their bones more to lighten their weight. By the end of the Cretaceous, birds flew over the heads of Tyrannosaurus Rex and other land-dwelling dinosaurs. Sixty-six million years ago, the birds and T-rex witnessed the Chicxulub impact that brought the Mesozoic to a close. While therapods with large and expensive body plans died out, birds sailed through to the Cenozoic. For this reason, we say that all non-avian dinosaurs are extinct, but dinosaurs are still very much with us – we call them birds.

Dignitary Locomotion in feet:

Theropod means “beast foot”, and for good reason. Adaptions in the metatarsals (foot bones) of theropods allowed them to walk with a digitigrade stance. Unlike humans that walk plantigrade (flat-footed), tyrannosaurus rex walked on their toes. Digitigrade motion has many benefits, as it allows the animal to run fast, increased agility and splayed toes offer better balance on muddy or slippery surfaces. Birds are coelurosaurs and inherited these anatomical characteristics from their theropodian ancestors. Chickens like tyrannosaurus rex walk with digitigrade locomotion, making them swift runners on land and providing excellent balance and stabilizing ability when resting on roosts.

Wish Bone:

The Thanksgiving tradition of “the lucky break” of the turkey wishbone is possible thanks to theropods who passed this anatomical trait to birds. In Tyrannosaurus rex, the furcula provided strength and power to the diminished but muscular forearms. In birds, the furcula fused from the two clavicle bones and function to strengthen the skeleton in the rigors of flight.

In conjunction with the coracoid and the scapula, it forms a unique structure called the triosseal canal, which houses a strong tendon that connects the supracoracoideus muscles to the humerus. This system is responsible for lifting the wings during the recovery stroke in flight.

S-shaped Skeleton:

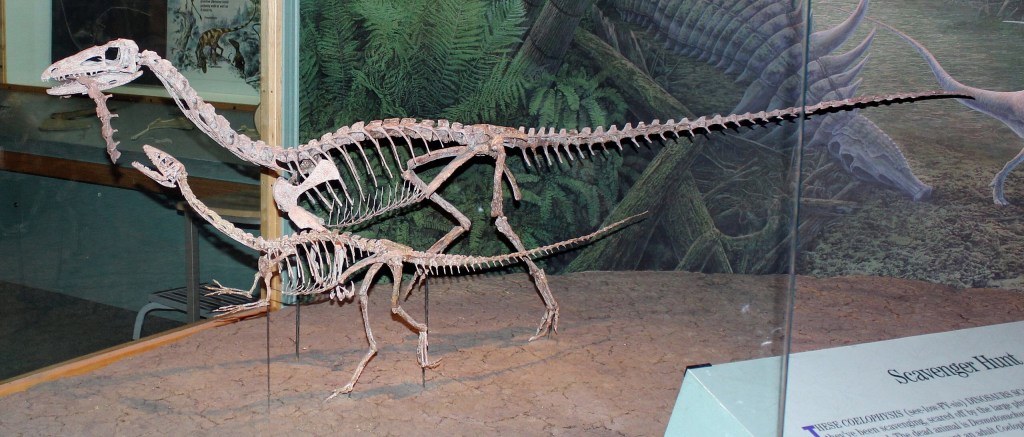

Chickens and all birds have a unique body plan visible in the skeleton. Comparing the skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex with modern birds will yield similar anatomical attributes. T-rex has a skull attached to a spine, ribs, and two legs with splayed toes providing swift bipedal locomotion. Focusing on the appendicular skeleton, we see that T-rex and modern birds have an S-shaped skeleton. The reason is that body plans do not have unlimited parts from which evolution can choose but rather build upon earlier ancestral shapes (Horner, 2009).

While birds lack teeth and long tails, the genes to manipulate these features still exist in the gene sequence of birds. In 2006, researchers at the University of Wisconsin published a report on manipulating the genes responsible for teeth in chicken egg embryos, resulting in buds that would later develop into crocodile-like teeth. The embryos were not allowed to hatch, but this research shows that the genes related to “dinosaur-like” features still exist within the genes of chickens; mother nature has just switched them off.

While it’s easy to say these features are of birds, they are not attributes of birds at all but are of dinosaurs.

By studying the anatomy of chickens and comparing these findings with the tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton, we see many of the same features. As we look closer, it becomes increasingly clear that T-rex is an overgrown chicken. Since the backyard chicken and the mighty T-rex have these characteristics in common, it stands to reason that these similarities are transferable to the study of tyrannosaur fossils, sexual dimorphism, and gender.

Medullary Bone in Egg Laying Hens:

In 2006, while studying bones of a newly discovered tyrannosaurus Rex, B-rex (Bob Rex, a tribute to the finder of this tyrannosaurus skeleton, Bob Harmon), a spongy-like mesh of tiny transparent flexible tubing was visible under a microscope. In attempts to determine the nature of this bone material, researchers turned to the closest living relative of the mighty T-rex – birds, specifically hens.

This bone medullary bone is a reproductive tissue found only in living female actively reproducing hens. As a hen advances to maturity, marked by egg laying, her body will produce medullary bone and continue to produce this bone throughout her laying duration. In some birds, this is seasonal in hens such as chickens; medullary bone is produced from her first egg at about 20 weeks of age throughout her subsequent laying lifetime. This reproductive bone tissue serves as mobilized calcium storage for the production of eggshells (Larson and Carpenter, 2008).

The hens in my backyard flock possess the same medullary bone discovered in B-rex. When my hens lay eggs, the shells that protect the egg are medullary bones stored in their bones. As she continues the lay year after year, this reproductive tissue replenishes. Since hens lay several eggs a week vs only seasonal, chicken feed is fortified with additional calcium to extend the egg potential of laying hens. While man’s attempts to lend support by increased calcium allow hens to produce stronger eggshells, the fundamentals are the same. My hens produce medullary bone because it is an attribute that they inherited from their ancestor, tyrannosaurus rex.

Unlike other bone types, medullary bone has no other function. It exists solely as a calcium storage for the production of eggshells. The formation of this reproductive tissue osteoclasts in the femur and tibiotarsus bones begins to deposit about 1 or 2 weeks before lay.

It’s a Girl!!!

The discovery of medullary bone found in the femur of MOR 1125, triggered by the increase of estrogen in her body, signified that this tyrannosaurus rex was not only a female but pregnant.

Living near the end of the 140-million-year reign of the dinosaurs, B-rex moved through the lush forests of a delta that fed several winding rivers in the Hell Creek Formation. She hatched 16 years prior, wandering about this tropical landscape, growing to maturity and preparing to mate.

Whether or not this was her first mating season, we do not know. Perhaps she died without ever producing offspring, or she was preparing to be a mother for the first time. We know that sixty-eight million years ago, she died young of unknown causes, and her burial was quick because her skeleton was well preserved.

The discovery of B-rex is the holy grail for paleontology and dinosaur studies. We can now assign gender and learn more about the intimate lives of tyrannosaurus rex specimens and other medullary bone-bearing dinosaurs through the lessons of B-rex, the pregnant T-rex.

I write at the confluence of deep time and modern thought – a paleontology blogger and essayist devoted to translating ancient worlds for contemporary readers.

Through Coffee and Coelophysis, I explore the lives, mysteries, and afterlives of prehistoric dinosaurs, blending scientific curiosity with reflective story telling. I bring ancient fossils to life; across my other writing spaces, I explore literature, creative reflection, homesteading, backyard chicken keeping, and the lessons of observations.

In Shelf-Life: Lessons from Retail, the everyday world of retail becomes a stage where dinosaurs, books, and human stories collide – revealing how curiosity and wonder shape both past and present.

Resources:

Brusatte, Steve. The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A History of Their Lost World. William Marrow of Harper Collins Publishers. New York, NY. 2018. Pgs. 282, 298, 299.

Harris P Matthrew, Hasso M Sean, Ferguson W.J. Mark, and Fallon F John. The Development of Archosaurian First-Generation Teeth in a Chicken Mutant. Current Biology Vol. 16, 371-377, February 21, 2006. URL

Horner, Jack. How to Build a Dinosaur. Plume, Published by Penguin Group. London, England. 2009. Pgs. 8,9,57, 58, 60.

Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth. Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. 2008. Pgs. 40, 93, 95, 98.

Randall K., David. The Monster’s Bones: The Discovery of T. Rex and How it Shook Our World. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York, N.Y. 2022. Pgs. 153.

~ Noelle K. Moser ~