Unveiling Giganotosaurus: The Prehistoric Rival of Tyrannosaurus Rex

email: noellemoser@charter.net

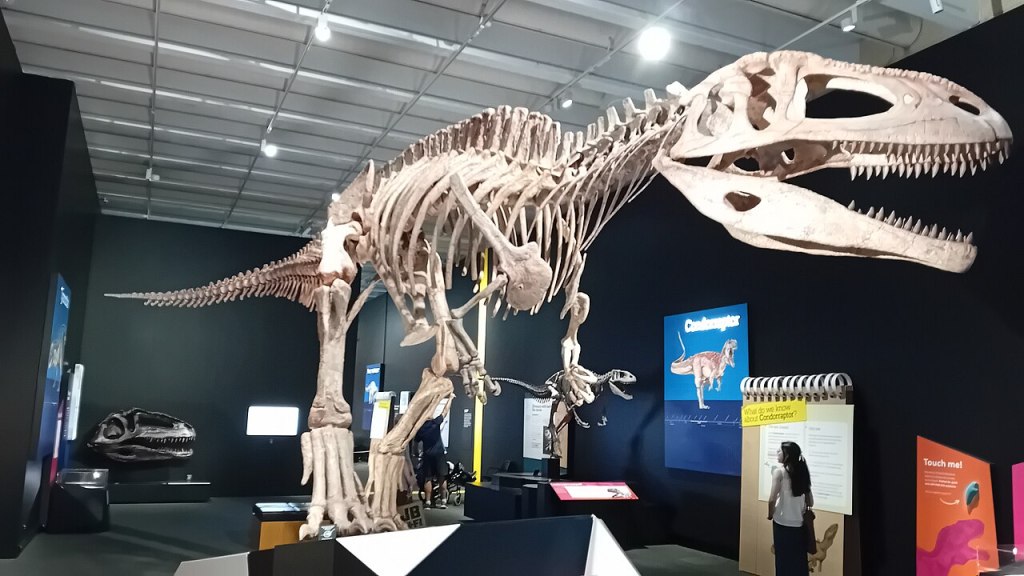

Boasting a skull as long as a man and a body the length of a bus, Giganotosaurus is among the largest predatory theropods ever discovered. Before Tyrannosaurus Rex reigned as the King of the Dinosaurs, a larger theropods dominated the prehistoric landscape. His name Giganotosaurus Carolinii.

Known as the “Giant Southern Lizard”, Giganotosaurus was a formidable predator that dominated the Southern Hemisphere. This massive theropod, a member of the Carcharodontosauridae family, hunted titanosaurs and other herbivores, establishing itself as one of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs, surpassing the mighty T-rex by 2.2 tons.

The tale of Giganotosaurus began in 1993 with the discovery of a tibia jutting from the earth in Patagonia. In 1994, paleontologists revealed the unearthing of a massive new theropod. The fossilized remains comprised a partial skull, a large portion of the vertebral column, elements of the pelvis, and fragments of limb bones.

The discovery of Giganotosaurus is important because it deepened our understanding of the Carcharodontosaurid clade. Producing some of the largest theropods to ever live such as the newly discovered Meraxes Gigas, Acrocanthrosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, and Giganotosaurus. This clade is of further interest to dinosaur enthusiasts because it allows us to explore the upper limit of theropod size.

Nature maintains a delicate balance between predators and prey. Large herbivores require equally formidable carnivores to sustain this balance. Giganotosaurus, a giant theropod, played a crucial role in the ecosystem where it lived. The real question is not whether Giganotosaurus hunted these massive herbivores, but how it did so. This article will explore the origins of the Giganotosaurus, its hunting strategies, and ultimately why it faced extinction.

Origins of Giganotosaurus:

During the Mesozoic, an evolutionary arms race between herbivores and carnivores ensued. As herbivores grew larger to gain a competitive advantage, the theropods also increased in size. The Jurassic period, marking the middle era of the age of dinosaurs, witnessed a remarkable diversification in dinosaur body plans. Herbivores grew larger, and thundering across the landscape were the sauropods, the giants of the Mesozoic era, including species such as Diplodocus and titanosaurs.

Giganotosaurus belongs to the Carcharodontosauridae family, a group of theropod dinosaurs known for producing some of the largest carnivores ever to walk the earth. Besides their massive size, a distinctive characteristic of this group is streamlined narrow skulls with shark-like teeth.

Teeth reveal much about a creature. By examining dinosaur teeth, we can determine their diet, hunting methods, and how they consumed their prey.

During the Jurassic, the middle period of the Mesozoic Era, there was a significant increase in size among species as a result of an evolutionary arms race between predators and prey. As herbivores grew larger, carnivores also evolved to match their size.

The Jurassic saw some of the largest and most famous herbivores – the sauropods. Species such as Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, Supersaurus, and Camarasaurus.

Counterparts to these lumbering giants, were the carnivores of the Jurassic, relatives of Giganotosaurus such as Tyrannotitan, Lusovenator, Siamraptor, and Acrocanthrosaurus.

Inhabiting the Southern Hemisphere, the relatives of Giganotosaurus, known as primitive Carcharodontosaurs, evolved into increasingly larger theropods in response to the growing size of the herbivores they preyed upon. By the end of the Jurassic and into the Early Cretaceous, the Carcharodontosauridae family comprised some of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs to have ever walked the Earth.

Giganotosaurus represented the culmination of an evolutionary arms race, standing as the pinnacle of the Carcharodontosauria clade.

How Giganotosaurus Hunted and Killed Prey:

Analysis of the leg bones of Giganotosaurus shows that this theropod was not built for speed, but it didn’t need to be. Although it was slower than the swift herbivores, Giganotosaurus preyed on the more ponderous sauropods, known as titanosaurs.

The titanosaurs were the last surviving group of long-necked sauropods, thriving at the time of the Chicxulub Impact at the end of the Cretaceous that ended the age of the dinosaurs. This group includes some of the largest land animals known to have ever existed, such as Argentinosaurus.

Titanosaurs lived by one rule, get big and get big fast. From the moment of hatching, sauropods like Argentinasaurus were eating machines. Dining on leaves and hard fibrous vegetation, a herd of titanosaurs could defoliate an area in a few days.

Large guts and hard-to-digest food allowed for a slow release of energy over time. This superpower aided in the ability of these sauropods to reach full size in less than ten years. Once fully grown, an adult Argentinasaurus was 128 ft long, 65 ft tall, and weighed 65 to 82 tons. This sheer size alone was enough to detour many theropods from making a meal out of these massive herbivores. Traveling in herds combined with size officially removed them from the menu.

Hunting a herd of titanosaurs was perilous. A single misstep can result in one of these colossal herbivores crushing an overzealous theropod, leading to instant death. Considering this risk, the question is not whether Giganotosaurus hunted titanosaurs, but rather how they accomplished such a feat.

Much like the enigmas posed by extinct species, the most effective way to address these questions is by examining the present. Observing lions as they hunt a herd of wildebeests, we see the predators collaborate to disperse the group, targeting the smaller, ill, or weakest members for an easier kill. A lion understands that to attack the largest, strongest, or healthiest would be, at best, a perilous endeavor. This logic can be similarly applied to Giganotosaurus.

Traveling herds exhibit remarkable organization. The young and subadults are positioned centrally, while the robust and healthy adults encircle them, forming a protective barrier. Typically, the elderly or injured members trail behind, comprising the rear guard as the herd moves across the terrain.

Understanding herd dynamics, a hunting Giganotosaurus would likely approach the herd from behind, targeting the weaker Argentinasaurus individuals. Despite not being in their prime, these titanosaurs remained formidable, capable of inflicting fatal injuries. It is probable that for these reasons, Giganotosauruses would hunt in packs, coordinating their efforts to take down one of these colossal creatures.

Evidence from the teeth of Giganotosaurus suggests that, unlike the bone-crushing bite of Tyrannosaurus Rex, Giganotosaurus had teeth better suited for slicing off flesh from its prey. Packs of Giganotosaurus would alternate in biting and slashing their prey, aiming to keep it moving and bleeding. The hunting strategy was to exhaust the prey through blood loss, fatigue, and infections caused by the theropods attacks, leading to the titanosaur’s eventual collapse under its own weight.

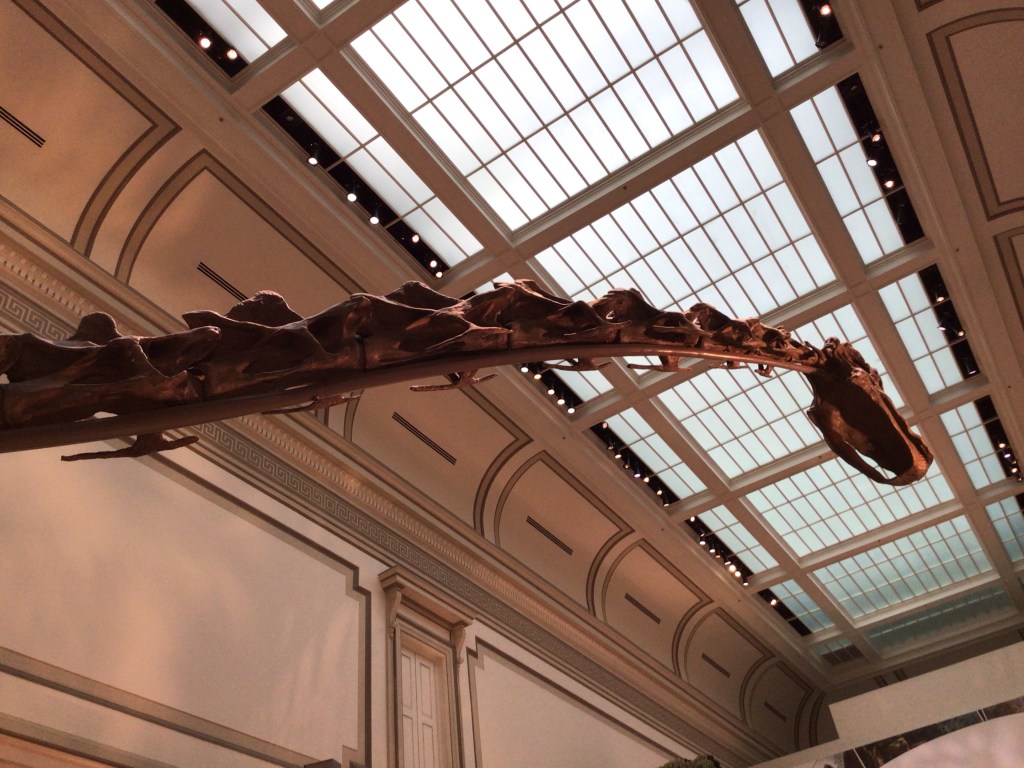

Trace fossils provide definitive evidence of theropod hunting strategies located along the Paluxy River near Glen Rose, Texas, USA. Here, a dramatic narrative of a dinosaur hunt is etched into the stone.

120 million years ago, on a muddy Cretaceous floodplain, the dynamics of dinosaur relationships were immortalized in stone. A herd of colossal sauropods lumbered along a waterway, stalked closely by a large carnivore. The pursuing theropod was focused, intent on the hunt.

Following behind the herd, slightly to the left, the theropod’s tracks indicate that the hunter rhythmically trailed the lumbering sauropods. Then the theropod’s footprints show that the hunter suddenly skipped a few steps, meaning only one thing, an attack.

Most of the trackway was removed. It is now preserved and displayed at The American Museum of Natural History in New York. Some of the trackway still remains submerged under the Paluxy River near Glen Rose, Texas.

Giganotosaurus Extinction:

Giganotosaurus lived during the Late Cretaceous period, specifically in the Cenomanian stage, approximately 99.6 to 97 million years ago. The reasons for its extinction are not definitive, but fossil records suggest several plausible scenarios. During the latter part of the Cretaceous, environmental changes due to plate tectonics posed survival challenges for Giganotosaurus and other Carcharodontosaurids.

Additionally, around 30 million years ago, Tyrannosaurs emerged as the dominant carnivores, with Abelisaurs prevailing in the Southern Hemisphere and Tyrannosaurus Rex in the northern. It is conceivable that Giganotosaurus was outcompeted by these more adaptable theropods, leading to a gradual decline and eventual extinction.

After the extinction of the last of the Carcharodontosaurs, Giganotosaurus lost its dominance, allowing the Tyrannosaurus and the formidable Tyrannosaurus Rex to rise as the King of the Dinosaurs until 66 million years ago when the age of the dinosaurs came to an end.

I am a multi-disciplinary writer, published author and web content creator. If you like this post, visit my other sites and online writing portfolio.

The Kuntry Klucker – A Blog about Backyard Chickens.

The Introvert Cafe – A Mental Health Blog.

Resources:

Johnson-Ransom, Evan. Dinosaur World: Over 1,200 Amazing Dinosaurs, Famous Fossils, and the Latest Discoveries from the Prehistoric Era. Applesauce Press. Kennebunkport, Maine. 2023.

Keiron, Pim. Dinosaurs The Grand Tour: Everything Worth Knowing About Dinosaurs from Aardonysx to Zuniceratops. The Experiment. New York, NY. 2019.

My visit to Natural History Museums across the nation.