Exploring the Houston Museum’s Dinosaur Treasures

Email: noellemoser@charter.net

Disclaimer: This article reflects my independent observations and insights gained during my research at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. I want to clarify that I am not affiliated with the HMNS in any capacity and have not received any compensation for writing this piece. The views and opinions expressed are solely my own. I am a professional writer and researcher specializing in dinosaurs. I travel to museums across the country to gather information and insights for my blog, where I explore the fascinating world of theropods and Mesozoic life.

The study of the Mesozoic era presents intriguing opportunities for exploration, particularly through its remarkable dinosaurs that once roamed the Earth. After thorough planning, which involved securing airline tickets and hotel accommodations, I recently visited the esteemed Houston Museum of Natural Science in Houston, Texas. This destination is celebrated for its exceptional paleontology exhibits, notably featuring three impressive specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex. The museum serves as a valuable resource for anyone interested in the fascinating history of dinosaurs and their environments during the Mesozoic era.

During my visit, I was truly moved by the incredible fossil collection on display. Multiple specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex, Acrocanthosaurus, Allosaurus, and Gorgosaurus brought a sense of excitement and connection to the past. As I explored the exhibits of herbivores—Diplodocus, Triceratops, Hadrosaurs, Ankylosaurus, and even a rare pair of Quetzalcoatlus—I couldn’t help but feel a deep sense of wonder. It reminded me of the rich history these magnificent creatures represent and the awe they evoke, connecting us to a world we can only experience through bone.

As someone profoundly captivated by Tyrannosaurus Rex, I dedicate my work to exploring its evolution, adaptations, and the mysteries of its lifestyle, making this visit truly meaningful. Houston is home to specimens of Stan, Bucky, and Wyrex—famous T-rex individuals that each tell a unique story about the life and evolution of this apex predator. Studying these fossils up close allowed me to dive deeper into their adaptations, pathologies, and mysteries.

Beginning with The Morian Hall of Paleontology, visitors are offered an engaging exploration of prehistoric life through a diverse collection of fossils and visual displays. This innovative exhibition presents the concept of deep time in a way that accommodates various learning styles, making it an informative experience for a wide range of audiences.

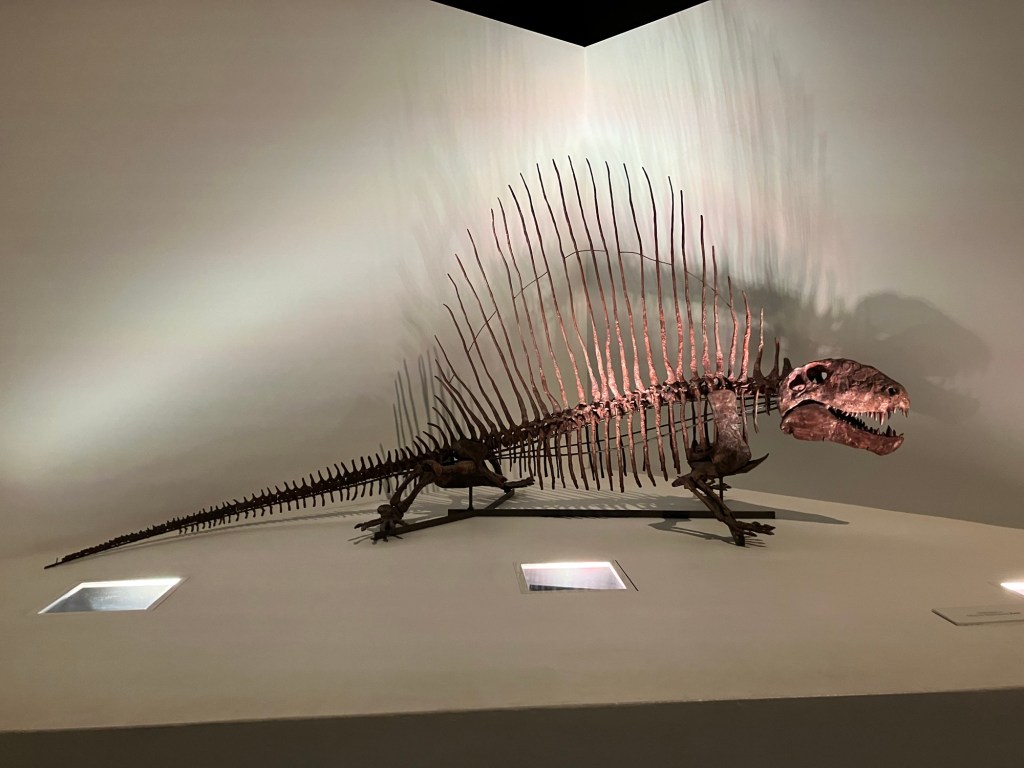

Immersed in a journey through deep time, visitors will encounter a variety of familiar prehistoric creatures. Notable among these are trilobites, which were marine arthropods, and ammonites, known for their coiled shells. The path also features early tetrapods, the four-legged ancestors of amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Additionally, one might come across impressive Devonian giant fishes such as Dunkleosteus, as well as the Permian period’s Dimetrodon. Another significant creature to observe is the notable Triassic archosaur Postosuchus, an ancient reptilian predator.

Entering the dinosaur hall, visitors are welcomed by the impressive cast of “Big Al,” the renowned Allosaurus that represents the pinnacle of Jurassic predators. Discovered in 1991 at the Howe Quarry in the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, “Big Al” is not only the most complete and well-preserved specimen of its kind but also a symbol of resilience. The pathologies revealed in this remarkable skeleton tell a powerful story of survival, showcasing evidence of injuries, diseases, broken bones, and the remarkable bone growths that came in response to adversity. “Big Al” inspires us to appreciate the strength and tenacity found in nature’s history.

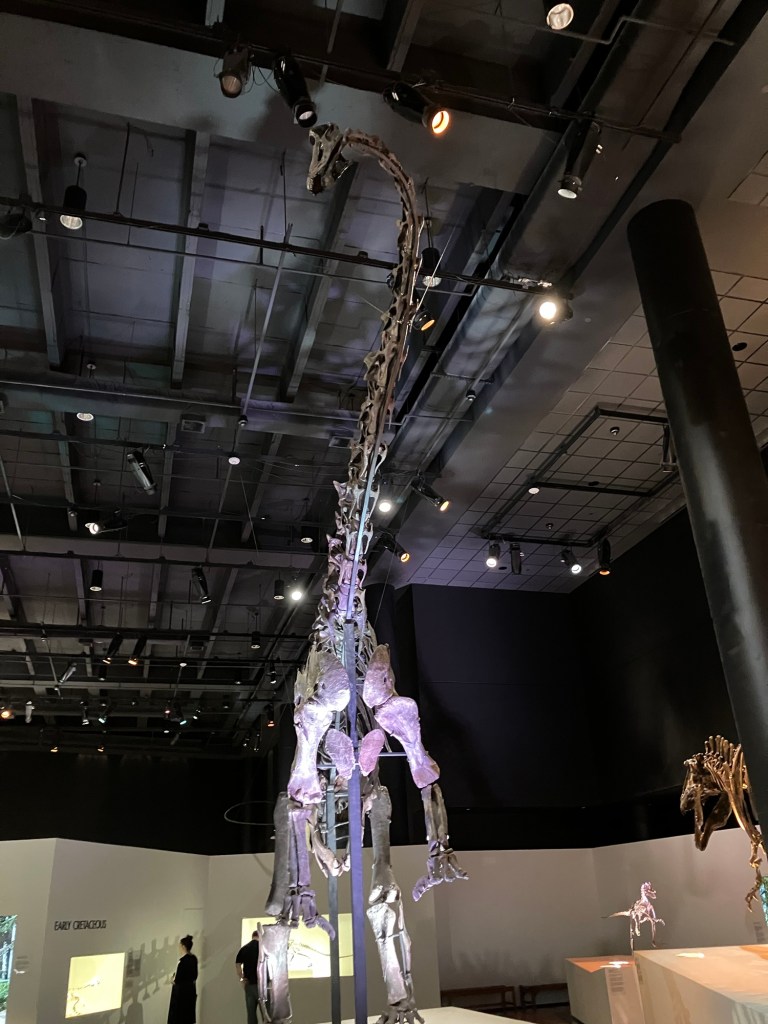

Stepping into the Paula and Rusty Walter Mesozoic Gallery, one is in awe of the vastness of space and the magnificent creatures that once roamed the Earth. Towering at the center is a Diplodocus rearing on its hind legs, long neck, and head stretching to the ceiling.

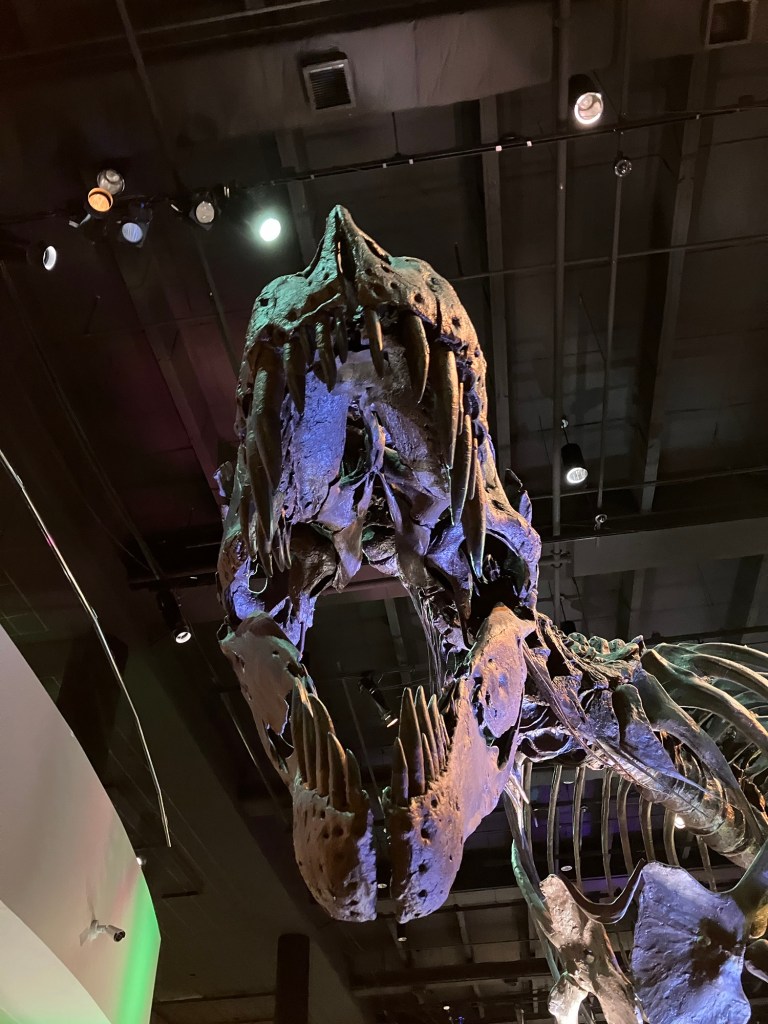

In various life-like poses stand a variety of large theropods and herbivores, each telling a story of the past. Most notable, and the reason for my venture to the Houston Museum of Natural Science, is BHI 3033, “Stan.”

Stan: The Tyrant Lizard King with Multiple Injuries

Stan, a remarkable specimen found in 1987 in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, serves as a beacon of discovery for paleontology and the biology of Tyrannosaurus rex. His fossil includes the most complete T. rex skull, a testament to the wonders of the natural world. Beyond the skull, Stan’s remains consist of 190 bones, representing about 63% of the entire skeleton, offering invaluable insights into the anatomy, lifestyle, and pathologies of one of the most intriguing Tyrannosaurus rex specimens in history. (Larson, 2008)

An examination of Stan’s bones reveals multiple pathologies and healed injuries sustained throughout his life. Puncture wounds on the back of his skull and ribs suggest he was at one time bitten by another Tyrannosaurus Rex. Bite marks at the base of his skull indicate a significant neck injury, leading to the fusion of two vertebrae, likely causing him pain for the remainder of his life. Holes on the side of his skull suggest more healed wounds and possible infections from bone-eating parasites. Stan’s pathologies show that life in the Cretaceous was challenging, even for a Tyrannosaurus Rex.

In a poised stalking stance with jaws gracefully agape, Stan proudly displays his formidable set of 60 teeth. Like all Tyrannosaurus rex specimens, he embodies extraordinary evolutionary development in dentation, demonstrating the power to overcome even the most daunting challenges in his quest for survival.

Examining Stan in such an accessible manner has given me a deeper insight into his life through his skeletal remains. Despite suffering severe injuries and pain, Stan’s capacity for healing and survival is a testament to the extraordinary resilience and robustness of this theropod. While the bone analysis of Stan shows healing, another T-Rex was not as lucky.

Wyrex: The Bob-tailed T-Rex.

Discovered in 2002 within the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and transferred to the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS) in 2009, the fossil known as “Wyrex” is an extraordinary Tyrannosaurus rex specimen. This groundbreaking discovery unveils a remarkable partial braincase and two nearly complete legs and feet, providing exhilarating new insights into the foot anatomy of the legendary Tyrannosaurus rex! (Larson, 2008)

Mounted in an attack stance adjacent to an Ankylosaurus, it is readily apparent that one-third of the tail is absent. As a critical component of Tyrannosaurus rex anatomy, the tail serves as a counterbalance to the skull and accommodates powerful musculature necessary for locomotion.

Analysis of the bone indicates no evidence of healing, suggesting that the tail may have been severed post-mortem, or that this injury ultimately unalived Wyrex. Had Wyrex survived this injury, the T-rex would have required a significant period of rehabilitation to regain the ability to walk effectively.

Presented in an assertive attack stance, Wyrex offers visitors an exceptional opportunity for a detailed examination of its distinctive conical, serrated teeth. This close-up perspective not only showcases the impressive anatomy of this prehistoric predator but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the evolutionary traits that contributed to its role in the prehistoric ecosystem.

In addition to its other remarkable features, Wyrex has yielded another significant discovery: several patches of fossilized skin from the Tyrannosaurus rex. This finding marks the first time that such skin has been uncovered for this iconic dinosaur, providing new insights into its biology and appearance. (Larson, 2008).

Bucky: A Female Teenage T-Rex.

The final Tyrannosaurus Rex showcased in the Paula and Rusty Walter Mesozoic Gallery is a sub-adult female TCM 2001.90.1 “Bucky”. Discovered in 2001 in the Hell Creek Formation by a rancher who, while breaking in a young horse, spotted the bones that led to this remarkable find, just 8 miles from where another robust female T-rex, Sue, was unearthed. (Larson, 2008)

Bucky plays a significant role in our understanding of Tyrannosaurus rex, as this remarkable fossil includes one of three most complete T-rex tails. It serves as a poignant reminder of the devastating injury that Wyrex endured, allowing us to reflect on the challenges a Tyrannosaurus rex faced in their lifetime.

As a sub-adult, juvenile teenage T. rex, Bucky provides valuable insights into the growth rates and different stages of maturity in the morphology of this iconic theropod. Bucky’s development illustrates the physical changes that occur as T. rexes progress from juveniles to adults, helping us understand their life cycle better.

Acrocanthrosaurus:

My journey to the Houston Museum of Natural Science would be incomplete without highlighting one last impressive theropod: Acrocanthosaurus. Most likely belonging to the Carcharodontosaur clade, a group of formidable predatory dinosaurs that thrived during the Aptian stage of the Early Cretaceous period.

Acrocanthosaurus stands out for its remarkably high neural spines, believed to have formed a striking sail along its back during its time on Earth. This formidable theropod once roamed ancient landscapes alongside colossal titanosaurs, majestic giants among the largest creatures ever to grace the Earth. Imagining these giant beasts sharing the same world ignites a sense of wonder and inspiration!

Studying dinosaurs is not just a passion; it’s a profound calling to uncover the mysteries of their world and our planet. My research leads me to natural history museums across the nation, with each destination unveiling new insights into the fascinating realm of dinosaurs and deepening my admiration for these incredible creatures.

This visit highlighted the fascinating aspects of Tyrannosaurus Rex and reinforced the reasons behind their enduring appeal. It’s not merely their impressive size and strength; rather, the complex details of their existence contribute significantly to their allure. The experience provided an exceptional opportunity to observe a diverse array of theropod evolution and variety all in one location. Most importantly, the Houston Museum of Natural Science offers tangible access to the wonders of prehistoric Earth, connecting us to a lost world we can only experience through bone.

To watch a video of my trip to HMNS please visit my YouTube Channel.

I write at the confluence of deep time and modern thought – a paleontology blogger and essayist devoted to translating ancient worlds for contemporary readers.

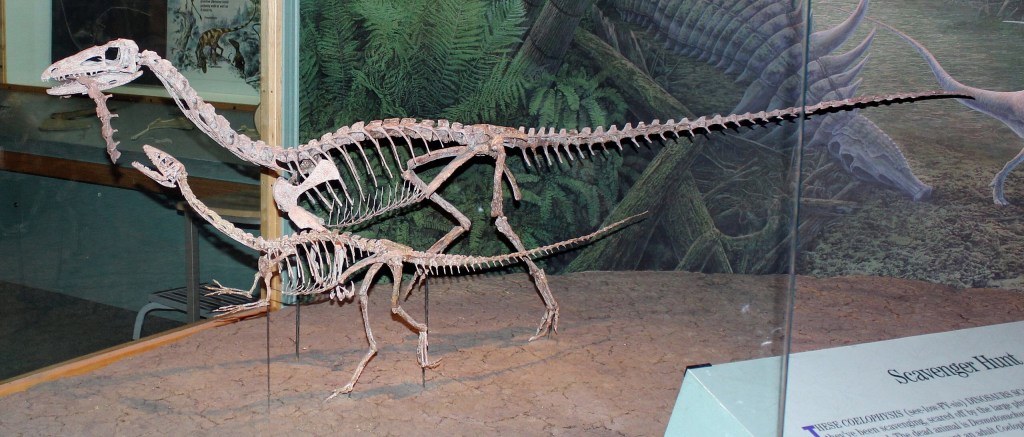

Through Coffee and Coelophysis, I explore the lives, mysteries, and afterlives of prehistoric dinosaurs, blending scientific curiosity with reflective story telling. I bring ancient fossils to life; across my other writing spaces, I explore literature, creative reflection, homesteading, backyard chicken keeping, and the lessons of observations.

In Shelf-Life: Lessons from Retail, the everyday world of retail becomes a stage where dinosaurs, books, and human stories collide – revealing how curiosity and wonder shape both past and present.

Resources:

Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth. Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. 2008.

Pim, Keiron. Dinosaurs the Grand Tour: Everything Worth Knowing About Dinosaurs from Aardonys to Zuniceratops. The Experiment. New York, NY. 2019.

My Visit to Houston Museum of Natural Science in Houston, Texas.