I have always valued ecosystems, not just as biological systems, but as intellectual ones. Habitats shape behavior, environments sculpt thought, and the landscapes we place ourselves in – prehistoric or modern – become the soil from which ideas grow. One ecosystem that has quietly influenced my writing life, and one I do not speak about nearly enough, lives not in a museum nor in the field, but on my desk. My desktop aquarium.

Simple in scale, yet vast in implication, it is a contained world – a glass biome- illuminated beside my keyboard. Within it, live species whose evolutionary histories stretch back millions of years. Lineages that survived mass extinctions including the Chicxulub Impact that ended the reign of the giant dinosaurs. Anatomies refined by ancient waters long before mammals ever walked on land. And yet, here they are, gazing, hovering, and navigating a world I assembled piece by piece. There is something mesmerizing about that.

The tank operates like a living cross‑section of time. A dark substrate lays the benthic base, plants rise in vertical green, territories carve themselves out, corridors take form, and shelter grows into the spaces between. Bubbles ascent in soft, rhythmic chains, a vetrivel current marking the passage of unseen chemistry.

Through this layered environment moves my fish, a single, bright organism threading itself through the foliage like a living brushstroke. When I pause my writing to watch it, I’m not escaping thought—I’m entering it. Observation slows the mind the way fossil study does, revealing patterns: routes repeated, resting places chosen, feeding rhythms kept, and the quiet intervals between motion. In that stillness, the mind begins to think ecologically—niches, energy, expenditure, spatial awareness, survival strategy—and in doing so, it settles.

In this way, my aquarium mirrors the prehistoric ecosystems I study and write about so often. The scale is smaller, but the principles are identical. Life organizes itself around resources, shelter, competition, and adaption – whether in a Late Cretaceous floodplain or a ten-gallon glass aquarium.

Even the aesthetics echo deep time. Coral-like structures evoke reef systems, shell forms recall molluscan longevity, and aquatic plants sway like submerged Mesozoic forests. It is a miniature ancient world – stylized, curated, but alive. What fascinates me the most, however, is where this biome is situated. Not across the room, but beside my keyboard.

My desk has become an ecosystem of its own books stacked like geological strata, stationery scattered like ground cover, soft lights glowing like bioluminescent fungi, a cultural reef encircling a living aquatic core. In this small biome, imagination and evolution coexist.

I write about theropods while watching fish whose ancestors once swam beneath them. I draft essays on extinction while observing survival unfold in real time. My thoughts drift between fossil bonebeds and the gentle pulse of filter currents, creating a strange but beautiful overlap of eras: deep past, living present, written reflection, all within arm’s reach. There is comfort in tending a small world. Feeding, cleaning, and monitoring it restores balance. It reminds me that ecosystems—no matter their scale—depend on stewardship, attention, and the willingness to notice subtle shifts before collapse. Perhaps that is why it shapes my writing more than I admit.

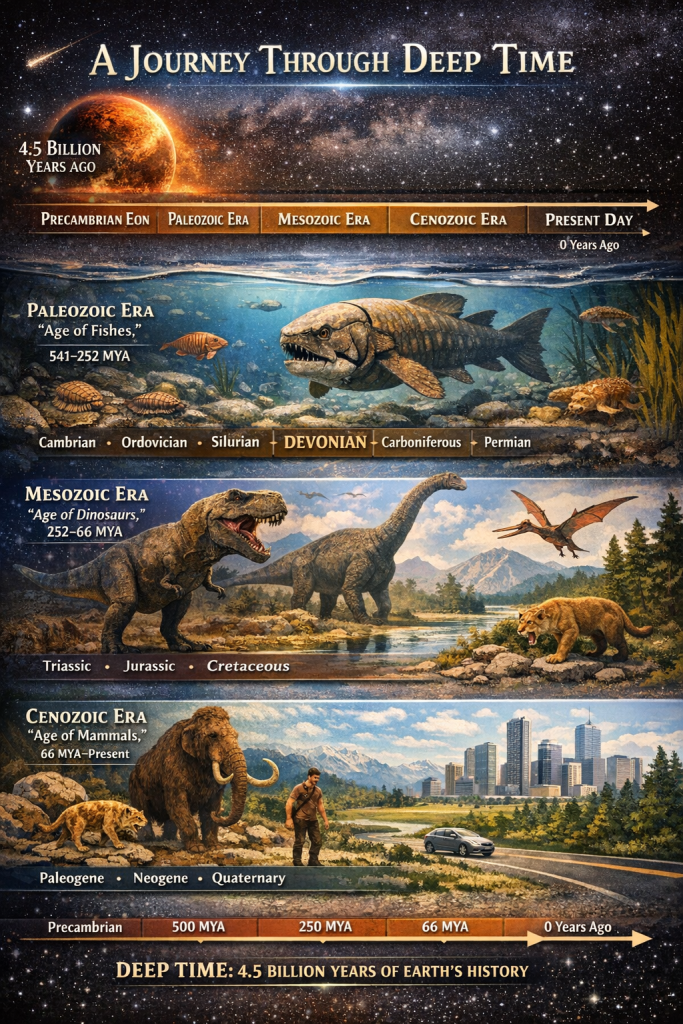

The lineages swimming before me did not begin in this tank, nor even in the age of dinosaurs. Their evolutionary blueprints were drafted in waters far older – in the Devonian, the great “Age of Fishes”, when vertebrate life was still experimenting with armor, jaws, and dominance in the sea.

It was a world where fish did not merely inhabit ecosystems, they ruled them. And among the most formidable of these rulers was Dunkleosteus – an armored placoderm titan whose very anatomy spoke of escalation. Encased in bony plating, equipped with self-sharpening jaw blades instead of teeth, it moved through Devonian seas as an apex force, a predator built not for grace, but for crushing authority.

Dunkleosteus: Devonian Titan

To imagine the waters that Dunkleosteus ruled is to image a different philosophy of life – one defined by armor, pressure, and biomechanical innovation. Coral reefs teemed beneath, early sharks shared its domain, and entire tropic systems organized themselves around its presence.

Weighing around a ton and stretching nearly 20 feet long, Dunkleosteus sat firmly at the top of the Devonian food chain, one of the fiercest marine predators ever to live. Its bulk limited its speed, but its jaws more than compensated—delivering a bite both fast and devastating, nearly four times stronger than that of Tyrannosaurus rex. With a force estimated at 5,600 kg per square centimeter (about 80,000 pounds per square inch), it could tear prey apart in a single bite. At that size and power, its prey was whatever it chose.

Evolutionary Significance of Dunkleosteus, King of the Placoderms:

Dunkleosteus came from the placoderms – early armor‑plated fishes whose heads and thoraxes gleamed with bone while the rest of their bodies tapered into skin and scale. They were among the first creatures to wield true jaws, and for a time they ruled their seas. Yet their dynasty lasted only about 50 million years. Sharks, meanwhile, have held their lineage steady for nearly 400 million.

Placoderms like Dunkleosteus stand at a turning point in vertebrate history. They were among the first creatures to wield jaws, igniting the ancient arms race that reshaped marine life. Their bodies carried early experiments in armor, jaw design, and sheer scale. Though they vanished at the end of the Devonian, the ideas their bodies tested lived on in the fish that followed.

Legacy of Placoderms at my Desk:

The fish in my aquarium share no direct ancestry with Dunkleosteus; the placoderms left no living descendants. Their armored lineages vanished long before the ecosystems I examine in the fossil record. Yet watching my fish navigate their tank still feels like witnessing a continuation of the same evolutionary narrative. They belong to the broader clade of jawed fishes—groups that survived multiple extinction bottlenecks and environmental upheavals. They passed through the crises of the late Devonian, and millions of years later, their distant relatives would endure even the end‑Cretaceous event that eliminated the non‑avian theropods central to my writing.

So, while Dunkleosteus itself is gone – its armor silenced, its oceans vanished – the story of its age was not entirely extinguished. It continues, softened and scaled, alive in the quiet bodies moving through the small ecosystem on my desk. When I look at my aquarium now, I am not seeing placoderms – but I am seeing their distinct inheritors. Lineages that endured planetary catastrophes the great terrestrial predators I write about did not survive.

The fish before me are emissaries of continuity, descendants of oceans where armored giants once patrolled. Surviving not only the end – Cretaceous extinction, but of far older ecological upheavals stretching back toward the Devonian itself. It reframes the tank entirely. No longer just a desktop habitat – but a living archive of vertebrate persistence.

And sometimes, watching their quiet movements through the plants, it is impossible not to imagine the ghost of armored silhouettes moving through darker, deeper waters behind them. As if the age when Dunkleosteus ruled the seas had not vanished completely…but has simply softened, scaled down, and continued swimming into the present.

I write about theropods, apex predators of vanished landscapes, while watching fish whose ancestors outlived them. I draft essays on extinctions while observing survival glide silently through plants. It creates a humbling recalibration of deep time. Because extinction is not universal, it’s selective, and survival is not about dominance, it’s about adaption to catastrophe.

Sometimes, when the room is quiet and the aquarium light is the brightest thing in my peripheral vision, I stop trying entirely and just watch. In those moments, the centuries between the Mesozoic and now feel thinner. As if two evolutionary stories – one ended, one ongoing – are sharing the same desk.

Beside my keyboard swims a lineage that survived the asteroid – while in my screen roam the predators that did not. Between glass and fossil, I write in the space where extinction and survival meet.

To write between worlds is to live with one foot in deep time and the other in the present moment – ink-stained fingers translating vanished oceans and thunderous footfalls into human language. It is both an exile and a privilege. In tracing the shadows of ancient life, I have come to better understand my own – my place in the long continuum of story, extinctions, survival, and wonder.

There is a personal truth I carry away from writing in these limited spaces, it is this: that the past is never truly gone. It breathes through my curiosity, words, and need to remember. And in giving voice to worlds that no longer exist, I have found a clearer voice for my own.

I write at the confluence of deep time and modern thought – a paleontology blogger and essayist devoted to translating ancient worlds for contemporary readers.

Through Coffee and Coelophysis, I explore the lives, mysteries, and afterlives of prehistoric dinosaurs, blending scientific curiosity with reflective story telling. I bring ancient fossils to life; across my other writing spaces, I explore literature, creative reflection, homesteading, backyard chicken keeping, and the lessons of observations.

In Shelf-Life: Lessons from Retail, the everyday world of retail becomes a stage where dinosaurs, books, and human stories collide – revealing how curiosity and wonder shape both past and present.

RESOURCES:

Mehling, Carl. Dinosaurs. Amber Books Ltd and United House. London. 2017.

Smithsonian. Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life. DK Publishing. New York, NY. 2019.